Why are Tibetans setting themselves on Fire?

An extract from Tibetan activist Tsering Woeser's Tibet on Fire: Self-Immolations Against Chinese Rule, translated by Kevin Carrico. This extract was originally published in the New York Review of Books.

February 27, 2009, was the third day of Losar, the Tibetan New Year. It was also the day that self-immolation came to Tibet. The authorities had just cancelled a Great Prayer Festival (Monlam) that was supposed to commemorate the victims of the government crackdown in 2008. A monk by the name of Tapey stepped out of the Kirti Monastery and set his body alight on the streets of Ngawa, in the region known in Tibetan as Amdo, a place of great religious reverence and relevance, now designated as part of China’s Sichuan Province.

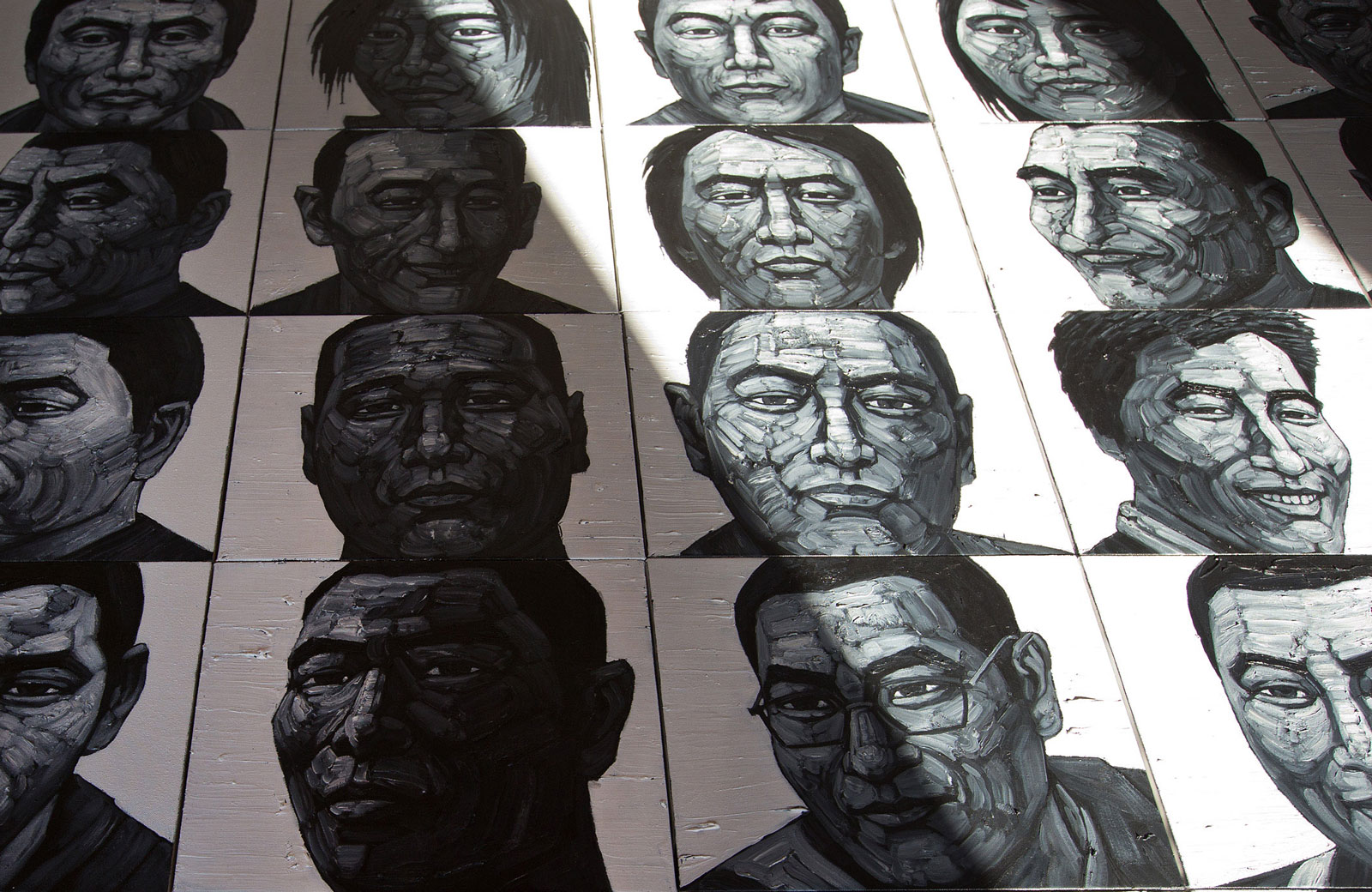

At least 145 other Tibetans have self-immolated since then. Of these, 141 did so within Tibet, while the remaining five were living in exile. According to the best information we have, 125 have died (including 122 within Tibet and three abroad). Most of these individuals are men, though some are women. Many were parents who left behind young children. The oldest was sixty-four, and the youngest was sixteen. Seven underage Tibetans have either self-immolated or attempted self-immolation; two of them died, and two were detained and their fate is unknown. The numbers include three monks of high rank (tulkus, or reincarnated masters), along with thirty-nine ordinary monks and eight nuns. But many were ordinary people: seventy-four were nomads or peasants; among the others were high school students, workers, vendors, a carpenter, a woodworker, a writer, a tangka painter, a taxi driver, a retired government cadre, a laundry owner, a park ranger, and three activists exiled abroad. All are Tibetan.

These events constitute the largest wave of self-immolation as a tool of political protest in the modern world—yet there is no such tradition in Tibetan history. How did we get here?

Recent decades have brought increasingly extreme oppression to Tibet’s third generation under Chinese rule. This oppression is primarily manifested in five areas of Tibetan life. First, Tibetan beliefs have been suppressed, and religious scholarship has been subjected to political violence. The dispute over the reincarnation of the tenth Panchen Lama in 1995, in which Beijing selected its own Panchen Lama and placed the Dalai Lama’s chosen appointee under house arrest, created the world’s youngest political prisoner and produced an irreparable break in relations between Beijing and the Dalai Lama.

A similarly paranoid decision in 2008 to expel all monks who were not born and raised in Lhasa from the city’s three main monasteries (Drepung, Sera, and Ganden) was one of the main factors leading to the protests that spread throughout the region that March. After the 2008 protests, a “patriotic education” program, forcing monks to denounce the Dalai Lama openly, was intensified and expanded beyond Lhasa to cover every monastery across Tibet. Outside of the temples, the people of Tibet face regular searches of their residences: images of the Dalai Lama are confiscated from their homes, and there have even been cases of believers being imprisoned simply for having a photograph of His Holiness.

Read the rest of the extract at NYR Daily.

For more information on Tsering Woeser's Tibet on Fire, click here.