Le Corbusier’s architectural fascism

A slew of new releases on the life of the architect Le Corbusier have shone a light on his fascistic leanings and the apologists who still defend him. In this polemical piece, originally published in Le Monde, Marc Perelman, wonders why organisations like Le Corbusier Foundation and the Pompidou Centre, where a new retrospective of his work is exhibited, has failed to confront these facts.

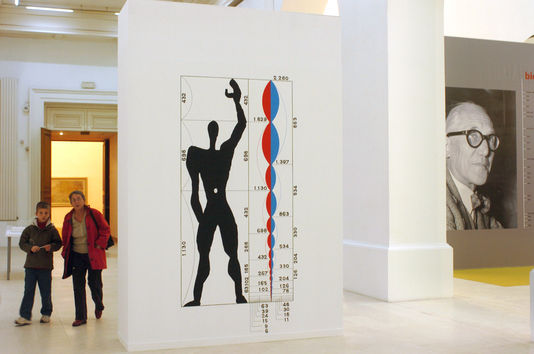

An exhibition dedicated to Le Corbusier at the Musée des beaux-arts de Nantes in 2006

It’s no longer a rumour, but a proven fact. From the 1920s up till the mid-1940s Le Corbusier contributed to a series of far-right, fascistic and fascist publications, most of which were anti-semitic and some of which were racist. All of them were anti-parliamentary, ultra-nationalist, and railed against democracy while fuming over so called racial degeneration…

These facts, revealed in three recent works – even if the Le Corbusier Foundation and the Pompidou Centre’s exhibition ‘Le Corbusier, Mesures de l’homme’ still have the brass neck to refuse to recognise them – have unleashed a wave of hard-fought polemics, which aren’t about to die down. (The works in question are Le Corbusier, un fascisme français, by Xavier de Jarcy, Albin Michel, 288 pages, 19 euros; Un Corbusier, by François Chaslin, Seuil, 517 pages, 24 euros; and Le Corbusier, Une froide vision du monde, by Marc Perelman, Michalon, 255 pages, 19 euros).

The institutions have reacted with anger and even contempt; numerous individuals who feel under attack have over-reacted, their scorn also blended with a degree of worry. Revelations like this always cause a stir, the now-demystified ideological leader’s epigones mortified that their supremo has been stripped bare. And that’s what’s happening today with Le Corbusier: they tell us that while he may have had foul ideas he was nonetheless a humanist, a poet, a visionary who wanted human happiness. It’s just like in the cases of Coubertin – he may have been a racist and a champion of colonialism, but he did after all magnificently reinvent the Olympic Games… - and of Heidegger, a Nazi but an immensely important philosopher… The rhetorical efforts of the sect-followers defending their ‘Master’ directly bring us back to the concept of false consciousness. They work by way of omission, prettifying, minimisation or forgetting (principally through the silencing of Le Corbusier’s political positions, said to have had nothing to do with his creative genius…); denial (misrepresenting or deriding critical arguments); or justification (his era created a difficult or complex if not unbearable situation, and that’s the unavoidable cause of the crisis…)

The culture of making excuses

We can see such rhetorical efforts at work in Paul Chemetov’s 30 April Le Monde piece. First he resorts to denial, saying ‘Le Corbusier was not a fascist’; then he tells us that ‘that was the time he lived in: it was a complicated situation’; and finally he opens up ‘All architects were Vichyites in those days’. Each moment of his reasoning ignores the one that went before; the universe of this reasoning does not belong to the world of dialectics. It is the universe of bad abstraction.

Paul Chemetov even verges on outright rambling, drawing an equals sign between Sartre, Camus and Le Corbusier simply because all of them were writing during the Second World War. The architect forgets that Sartre and Camus weren’t making anti-semitic arguments, did not throw themselves into the arms of Vichy, and did not lick the boots of Marshal Pétain.

The exhibition ‘Le Corbusier. Mesures de l’homme’ (and the catalogue that was produced for it) ought to have been a triumph, providing the space for a public debate. It was not. Not in terms of how it was arranged and the results of the considerable resources devoted to it, but, more fundamentally, the fact that it set in parentheses the political context in which – and of course, through which – Le Corbusier thought, planned, built and defended his own works.

But how can you present such a litany of objects, while taking them out of the political context in which they were produced? How can you forget the political backdrop of the interwar period? That’s a really tricky one. Unless those who commissioned it were breathing in the air of our own era so much that they deliberately produced an exhibition and a catalogue that were decontextualised from any history and any link with the socio-political forces of Le Corbusier’s time, not making any reference to the architect’s ideological positions. Yet Le Corbusier’s aesthetic has its origins in the worst positivist, reductionist and reactionary conceptions of his era. They keep telling us about Gustav Fechner’s ‘psychophysics’, which Le Corbusier used for his own purposes, but even Henri Bergson criticised this philosophical current; any psychic measurement that claims to be scientific is a theoretical imposture.

The ‘Modulor’ at the centre of his work

If the theme, or rather the object of this exhibition – the body – was indeed at the heart of Le Corbusier’s architecture, it is completely misrepresented by the two curators who took charge of the catalogue. Far from celebrating the body as a site of pleasure, well-being or joy – still less of possible emancipation and liberation – Le Corbusier reduces it to a set of numbers, transforming it into an instrument of measurement and flattened proportions, a means of sporting performance. All this is deeply encrusted in the way the architect thinks about corporeality, with a cold cutting-up of the body, a mechanistic division or even a kind of biological mysticism (the regenerated body, purity, human nature…) So we can say that architecture and Le Corbusier’s city resound with a sort of ‘grip on the body’, truly a ‘policy of coercions that act upon the body, a calculated manipulation of its elements, its gestures, its behaviors’, since ‘the body becomes a useful force only if it is both a productive body and a subjected body’ (Michel Foucault).

If architecture and the city can only be understood with reference to their corporeal roots, for Le Corbusier the body is overdetermined by a human essence that is itself forever overdetermined by an invariable: the Modulor. It is no chance thing that he first put the Modulor to work in 1943. This human silhouette, this muscular and partly reified body, this mechanical armour, is supposed to correspond to the construction of a new body, producing a space that Le Corbusier sees as tightly bound to definitive proportions that he abstractly defines on the basis of what are in fact widely varying bodily dimensions. The Modulor is above all a tool of measurement, which, embodied in man, adjusts the surrounding space to fit around his flesh as closely as possible. It imposes senseless geometrical norms on a supposedly universal body in order to create what the architect calls ‘constructed beings, cemented biologies’.

So much so that the housing cell, the housing unit, and the city itself, are conceived on the basis of a ‘Modulorised’ body, which is supposed to deploy an original spatial dynamic. Here in fact bodies are caught between their four walls, compressed by deliberately restricted but still tolerable proportions, kept in corridors provided with multiple shops, and trapped in the leisure and sporting facilities of the ‘Radiant City’ skyscraper and its grounds. This was after all a matter of ‘arranging dwellings that would be able to contain the inhabitants of the city, and above all to keep them there’, as the architect explained. The ‘equally-proportioned housing units’, as Le Corbusier defined them with so much poetry, were above all immense envelopes of rough-cast concrete, lifted above the ground by imposing, monumental, crushing pillars. They exercise a total pressure on the body, since the inhabitants must never leave except in order to join the traffic (this being one of Le Corbusier’s four functions of urbanism, together with working, living and recreation).

The housing unit: sport as prison

And when the inhabitants do leave their housing unit, they find themselves not in a natural space but directly confronted with immense sports facilities. These too are geometrically arranged, and capture whatever is left of the inhabitants’ energy in order to convert it into sporting acts and movements, thus turning them into automatons deprived of any spontaneity. After all, as the architect constantly repeated ‘if we do not want to equivocate over pressing realities, we need to organise sport at the foot of the houses … The human cell must therefore be complemented with common services, and sport becomes one of its everyday domestic manifestations’. Sport is also present within the housing unit, in the form of gym halls. So sport is everywhere. For Le Corbusier the stadium – the historic sporting facility par excellence – is already an outmoded form of spectacle, with its division between active athletes and passive spectators.

In the future, the whole radiant city must become a stadium, setting the masses in motion through their quasi-automatic self-enrolment. We are very far, here, from the body as pleasure and corporeal emancipation; rather, this is the body in chains, crushed and reduced to little dots that are close to regimented in a one-dimensional and uniform city of glass and concrete. Le Corbusier’s ideas on the body have nothing to do with any sort of humanism, with the freedom of the body and its mastery of its movements and acts within an open and boundlessly plastic space. His architecture and his urbanism (the Plan Voisin) are, quite the contrary, a prison organisation that goes beyond sociology and politics to create a single body trapped by the technology of the modern building, a machine body in a vast ‘housing machine’, a malleable clay in the hands of the architect-demiurge and fascist.

I want to insist on the fascist character of the body as conceived by Le Corbusier. Fascism and Nazism, like Stalinist Stakhanovism and neo-Stalinist puritanism, all rest on a rather similar mass corporeality. They apprehend the body as a block of muscles, a viriloid form, a sporting armour ready for engagement in violent social relations. Le Corbusier makes use of all these features, working them into his own outlook.

Metabolic fusion

So the very condition of individuals’ existence is linked to the submission of their bodies to the tyrannical regime of the carceral housing cell, enclosed in a huge block which is itself repeated over and over across a span of several kilometres. ‘You deny that a man – the guy with his two legs, his head and his heart – is an ant or a bee enslaved to the need to live in a box, a compartment behind a window; you call for total freedom, a total fantasy according to which each man would act in his own way, following a creative lyricism along always new and never beaten paths – individual, diverse, unexpected, impromptu and unspeakably fantastical ones. Well, no, here is the proof that man sticks to the box that is his bedroom and the window that opens to the outside world. This is a law of human biology: the square box, the bedroom, is a useful creation that humanity has devised’.

Le Corbusier’s architecture and his urbanism more broadly impose a rigid corporeal order, a conversion of free impulses, a new political alchemy of bodies under the regime of a sinister biological anchoring. The true power of Le Corbusier’s architecture and urbanism relates to its exhibitionist quality – it is spectacular on account of its use of rough materials, the concrete often covered in primary colours, the perfection of the straight lines, the advancement of an immense machinist collective technology, and the osmosis of bodies with the urban machine of which they are the cogs.

For Le Corbusier the big city ‘is the vital organ in the biology of a country: national organisation depends on it, and national organisations make up the international organisation. The big city is the heart, the active centre of the cardiac system; it is the brain, the directing centre of the nervous system …’ Biology is thus also part of the fantasy of a successful osmosis between the individual body and the city, or even a metabolic fusion. The body disappears. From the aesthetic point of view, artistic movements like Expressionism and Surrealism, for example – which Le Corbusier scorned – pointed an accusing finger against the established reality, and contributed to projecting an image of social liberation. These movements had a degree of autonomy, in the sense that they were able to tear art from its power to mystify the already-established and taken for given; they liberated art by allowing it to express a truth of its own (transcendence, otherness, complex manifestations of beauty). Conversely, Le Corbusier’s aesthetic contributed to the doubling of reality in simplified forms, able to fascinate on account of their systematising effect: the five points of the new architecture, the four functions of urbanism, etc.

- Marc Perelman is author of Le Corbusier. Une froide vision du monde, Michalon, 255 p., €19

Translated by David Broder. Visit Le Monde's website to read the full article in French