The Indians of Palestine: An interview between Gilles Deleuze and Elias Sanbar

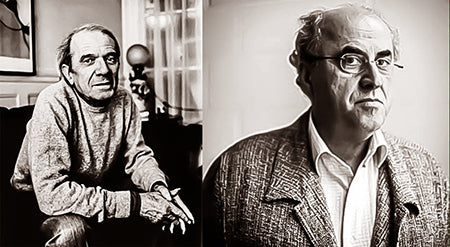

In 1982, the French philosopher Gilles Deleuze interviewed the Palestinian author Elias Sanbar, founder of the Journal of Palestine Studies (La Revue d'Études Palestiniennes). They examine the importance of the journal and the existence of the people and land of Palestine. Disgracefully, over 30 years later, these discussions are still despairingly relevant to today's climate.

We have waited a long time for an Arab journal in French, but instead of coming from North Africa, it's being done by the Palestinians. La Revue d'Études Palestiniennes has two characteristics obviously centered on Palestinian problems which also concern the entire Arab world. On the one hand it presents very profound socio political analyses in a masterful yet calm tone. On the other hand, it mobilizes a specifically Arab literary, historical and sociological "corpus" which is very rich and little known.

-Gilles Deleuze, 1982

Deleuze: Something seems to have ripened on the Palestinian side. A new tone, as if they have overcome the first state of their crisis, as if they have attained a region of certainty and serenity, of "right" {droit), which bears witness to a new consciousness. A state which allows them to speak in a new way, neither aggressively nor defensively, but "equal to equal" with everyone. How do you explain this since the Palestinians have not yet achieved their objectives?

Sanbar: We have felt this reaction since the appearance of the first issue. There are the actors who said to themselves, "look, the Palestinians are also doing journals like this," and that has shaken a well-established image in their heads. Don't forget that for many people the image of the Palestinian combatant for which we claim responsibility has remained very abstract. Let me explain. Before we established the reality of our presence, we were perceived as refugees. When our resistance movement established that our struggle was one to be reckoned with, we were trapped once again in a reductive image.

Multiplied and isolated to infinity, it was an image of us as pure militarists, and we were perceived as doing only that. It's in order to leave that behind that we prefer our image of combatants to that of militiamen in the strict sense.

I believe that the astonishment which the appearance of this journal has provoked also comes from the fact that certain people must now begin to admit to themselves that the Palestinians exist and that simply recalling abstract principles does not suffice. If this journal comes from Palestine, it nonetheless constitutes a terrain on which multiple pre-occupations are expressed, a place where not only Palestinians take the floor but also Arabs, Europeans, Jews, etc.

Above all, certain people must begin to realize that if there is such a labor as this, such a diversity of horizons, it probably must also include, at other levels of Palestine, painters, sculptors, workers, peasants, novelists, bankers, actors, business people, professors . . . in short, a real society, of whose existence this journal gives an account.

Palestine is not only a people but also a land. It is the link between this people and their despoiled land, it is the place where an absence and an immense desire to return are enacted. And this place is unique, it's made up of all the expulsions that our people have lived through since 1948. When one has Palestine in one's eyes, one studies it, scrutinizes it, follows the least of its movements, one notes each change which awaits it, one adds up all its old images, in short, one never loses sight of it.

Deleuze: Many articles in the Revue d'Etudes Palestiniennes recall and analyze in a new way the procedures by which the Palestinians have been driven out of their territories. This is very important because the Palestinians are not in the situation of colonized peoples but of evacuees, of people driven out. You insist, in the book you are writing, on the comparison with the American Indians. There are two very different movements within capitalism. Now it is a matter of taking a people on their own territory and making them work, exploiting them, in order to accumulate a surplus: that's what is ordinarily called a colony. Now, on the contrary, it is a matter of emptying a territory of its people in order to make a leap forward, even if it means making them into a workforce elsewhere. The history of Zionism and Israel, like that of America, happened that second way: how to make an empty space, how to throw out a people?

In an interview, Yasser Arafat marks the limit of this comparison, and this limit also forms the horizon of the Revue d’Etudes Palestiniennes: there is an Arab world, while the American Indians had at their disposal no base or force outside of the territory from which they were expelled.

Sanbar: We are unique deportees because we haven't been displaced to foreign lands but to the continuation of our "own place." We have been displaced onto Arab land where not only does no one want to break us up but where this idea is itself an aberration. Here I'm thinking of the immense hypocrisy of certain Israeli assertions which reproach the other Arabs with not having" integrated" us, which in Israeli language means "made us disappear".... Those who expelled us have suddenly become concerned about alleged Arab racism with respect to us. Does this mean that we have not confronted contradictions in certain Arab countries? Certainly not, but still these confrontations were not the results of the fact that we were Arabs; they were sometimes inevitable because we were and are an armed revolution. We are also the American Indians of the Jewish settlers in Palestine. In their eyes our one and only role consisted in disappearing. In this it is certain that the history of the establishment of Israel reproduces the process which gave birth to the United States of America.

This is probably one of the essential elements for understanding those nations' reciprocal solidarity. There are also elements which signify that during the period of the Mandate affair we did not have the customary "classical" colonization, the cohabitation of settlers and colonized. The French, the English, etc…wished to settle spaces in which the presence of the natives was the condition of existence of these spaces. It was quite necessary that the dominated be there for domination to be practiced. This created common spaces whether one wanted them or not, that is to say networks, sectors, levels of social life where this "encounter" between the settlers and the colonized happened. The fact that it was intolerable, crushing, exploitative, dominating does not alter the fact that in order to dominate the "local," the "foreigner" had to begin by being "in contact" with that "local." Then comes Zionism, which begins on the contrary from the necessity of our absence and which, more than the specificity of its members (their membership in Jewish communities), formed the cornerstone of our rejection, of our displacement, of the "transference" and substitution which Ilan Halevi has so well described. Thus for us were born those who it seems to me must be called "unknown settlers," who arrived in the same stride as those whom I called "foreign settlers." The "unknown settlers" whose entire approach was to make their own characteristics the basis of a total rejection of the Other.

Moreover, I think that in 1948 our country was not merely occupied but was somehow "disappeared." That's certainly the way that the Jewish settlers, who at that moment became "Israelis," had to live the thing.

The Zionist movement mobilized the Jewish community in Palestine not with the idea that the Palestinians were going to leave one day, but with the idea that the country was "empty." Of course there were certain people who, arriving there, noticed the opposite and wrote about it! But the bulk of this community functioned vis-à-vis the people with whom it physically rubbed shoulders every day as if those people were not there. And this blindness was not physical, no one was deceived in the slightest degree, but everyone knew that these people present today were "on the point of disappearance," everyone also realized that in order for this disappearance to succeed, it had to function from the start as if it had already taken place, which is to say by never "seeing" the existence of the other who was indisputably present all the same. In order to succeed, the emptiness of the terrain must be based in an evacuation of the "other" from the settlers' own heads.

In order to arrive there, the Zionist movement consistently played upon a racist vision which made Judaism the very basis of the expulsion, of the rejection of the other. This was decisively aided by the persecutions in Europe which, led by other racists, allowed them to find a confirmation of their own approach.

We think moreover that Zionism has imprisoned the Jews, it's taking them captive with this vision I just described. I'm saying that it's taking them captive and not that it took them captive at a given time. I say this because once the holocaust passed, the approach evolved, it was transformed into a pseudo-"eternal principle" that says the Jews are always and everywhere "the Other" of the societies in which they live.

But there is no people, no community which could claim- and happily for them- perpetually to occupy this position of the rejected and accursed "other."

Today, the other in the Middle East is the Arab, the Palestinian. And the height of hypocrisy and cynicism is the demand, made by Western powers upon this other whose disappearance is constantly the order of the day, for guarantees. But we are the ones who need guarantees against the madness of the Israeli military leaders.

Despite this, the PLO, our one and only representative, has presented its solution to the conflict: the democratic state of Palestine, a state which would tear down the existing walls separating all the inhabitants, whoever they may be.

Deleuze: La Revue d'Études Palestiniennes has its manifesto, which appears in the first two pages of Issue #1: we are "a people like others." It's a cry whose meaning (sens) is multiple. In the first place, it's a reminder or an appeal.

The Palestinians are constantly reproached for refusing to recognize Israel. Look, the Israelis say, they want to destroy us. But the Palestinians themselves have struggled for more than 50 years to be recognized.

In the second place, it's in opposition to the Israeli manifesto, which is "we are not a people like others," by reason of our transcendence and the enormity of the persecutions we have suffered. Hence the importance, in Issue #2 of the Revue , of two texts on the Holocaust by Israeli writers, on Zionist reactions to the Holocaust, and on the significance that the event has acquired in Israel, in relation to the Palestinians and the entire Arab world that were not involved in it. Demanding "to be treated as a people outside the norm," the state of Israel maintains itself all the more completely in a situation of economic and financial dependence upon the West such that no other state has ever known (Boaz Evron) . This is why the Palestinians hold fast to the opposite claim: to become what they are, that is, a completely "normal" people.

Against apocalyptic history, there is another sense of history that is only made with the possible, the multiplicity of the possible, the profusion of possibles at each moment. Isn't this what the Revue wants to show, even and above all in its analyses of current events?

Sanbar: Absolutely. This question of reminding the world of our existence is certainly full of meaning, but it's also extremely simple. It's a sort of truth which, when truly admitted, will make the task very difficult for those who have looked forward to the disappearance of the Palestinian people. Because, finally, what it says is that all people have a kind of "right to rights" (droit au droit). This is an obvious statement, but one of such force that it very nearly represents the point of departure and the point of arrival of all political struggle. Let's take the Zionists, what do they say on this subject? Never will you hear them say, "the Palestinian people have no right to anything," no amount of force can support such .a position and they know it very well. On the contrary you will certainly hear them affirm that "there is no Palestinian people."

It's for this reason that our affirmation of the existence of the Palestinian people is, why not say it, much stronger than it appeared at first glance.

Translated by Timothy S. Murphy for Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture: Vol. 20: Iss. 3, Article 4. Visit their website to subscribe to their journal.

Originally published in Libération, May 8-9, 1982 with the title Les indiens de Palestine

Further Reading:

The Case for Sanctions Against Israel is now available to download for free on our website. Read more on the horror of the Israel-Palestine conflict from Ilan Pappe, Shlomo Sand, Naji al-Ali and Ghada Karmi on our reading list.