Tariq Ali, Steve Smith, Trotsky and Serge

Susan Weissman responds to Steven Smith's letter to the LRB on Tariq Ali, Victor Serge and Trotsky.

In his response to Tariq Ali (“Inquisition Mode”, LRB, 16 July) Steve Smith writes that the period of Trotsky’s friendship with Serge was brief, and that relations between them deteriorated over contradictory arguments Trotsky expressed in two polemics, 18 years apart, about means and ends in revolution. But the relationship between Serge and Trotsky was closer, longer, and more complicated than Smith asserts, and their rift was less definitive, its causes more murky, than Smith allows.

Serge stood with the Left Opposition, led by Trotsky, from 1923 onwards -- in the open, in clandestinity, and through prison and deportation. They met and worked together in the USSR, from 1925 until the Left Opposition was expelled from the Party at the end of 1927. Serge was first arrested in 1928 and Trotsky was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1929. Though they were never able to meet face to face again, they corresponded frequently once Serge was released and expelled to the West in 1936.

In Paris, Serge worked with Trotsky’s son Leon Sedov to refute the charges of the Moscow Trials (1936-38), was the trusted translator of Trotsky’s works into French, including Revolution Betrayed, and was in every sense an ideal political collaborator, as Trotsky warmly acknowledged in their correspondence.

Differences between the two exiled Left Oppositionists developed from mid-1937 over their assessments of the nature of the period, which gave rise to different views of how to relate politically to the POUM in Spain, the Popular Front in France, the renewed debate over the suppression of the Kronstadt revolt of 1921, and, most importantly for Trotsky, the founding of the Fourth International. These were significant disagreements, but hardly unexpected within a small and beleaguered movement fighting Stalin and the rise of Hitler, and it is doubtful if in themselves they can account for the break, especially in light of the insidious intervention of the NKVD agent in their midst, Marc Zborowski, aka Etienne, in sowing discord and promoting scissions.

Smith argues that the relations between Serge and Trotsky “deteriorated beyond repair” over Trotsky’s arguments in Their Morals and Ours, specifically that Serge was unable to countenance Trotsky’s inability “to explain why methods used by the Bolsheviks during the Civil War,” which Trotsky had justified in his pamphlet Terrorism and Communism (1920), “became morally reprehensible when used by the Stalinist regime” in Their Morals and Ours (1938).

While the publication of Serge’s translation of Trotsky’s Their Moral and Ours did bring intensified controversy to their relationship, it wasn’t over the substance and content of the book, which Serge never publicly criticized. Serge did not want to stoke further unnecessary conflict with Trotsky, and on the question of means and ends in defending the revolution, Serge was sympathetic to Trotsky’s view.

With respect to Terrorism and Communism, Serge wrote “Trotsky in no way defends what is currently understood as terrorism, but rather demonstrates the working class’s absolute need, in those revolutionary periods where it must either win or die, to show itself strong and capable of using all the harshness of war…”

As to Their Morals and Ours, Smith admits that Trotsky “appeared to endorse the point made by Serge and other critics that there is a ‘dialectical interdependence of means and ends,’” the subtitle of the final section that Serge thought contained “fine and worthwhile pages.”

For Serge, historical context was all-important. There is a world of difference between the Bolsheviks’ conduct during the Civil War, when the besieged revolutionaries were fighting to preserve the world’s first successful socialist revolution against invading armies and internal counter-revolutionaries -- who themselves used terroristic methods against the revolutionaries, and Stalin’s conduct in what amounted to war against his own population in peacetime -- through forced collectivization, breakneck industrialization and mass terror during the Purges.

The worsening dispute with Trotsky was not over Serge’s translation or unspoken disagreements with Trotsky’s ideas, but over the crude promotional blurb attached to the French edition of Their Morals and Ours, surely written with NKVD guidance, if not directly by Zborowski (Etienne) himself. Trotsky unleashed a torrent of invective against Serge, assuming (without checking) that he had written the accompanying blurb. Serge protested that he did not write it, it was completely “at variance with his frequently expressed opinions,” and he had nothing to do with it.

The issue over which Trotsky and Serge ultimately broke was the founding of the Fourth International, and Trotsky did not hide his vexation at Serge and others who would not join in the project. Serge did take part in the founding of the Fourth International, even as he argued the timing was all wrong for creating a new international -- an international party of revolution in a time of defeat (fascism, war, Stalinist totalitarianism). Trotsky could not abide this defection.

The rupture between Serge and Trotsky was never really completed, and had the character of a quarrel with room for conciliation. Even as Trotsky attacked Serge publicly, he wrote warmly to him privately, saying he was ready to do anything to improve their collaboration -- on the condition that Serge join the Fourth International. Serge understood Trotsky’s inflexibility without agreeing to his condition, because he saw the Old Man as “the last survivor of a generation of giants,” isolated in his Mexican exile, no longer in contact with comrades of the same stamp as himself “men who could understand his unspoken thoughts and could argue on his level.”

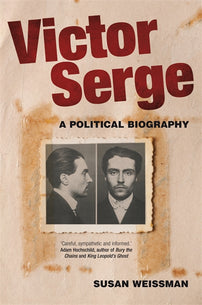

Susan Weissman is the author of Victor Serge: A Political Biography (Verso 2013)

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]