Politicising depression during a pandemic

The Coronavirus pandemic has confined us to our households, caused thousands to lose their jobs and spread debilitating panic and despair. Calls to crisis helplines are surging and the majority of us are feeling anxious or low. But, Sian Bradley asks, can politicising these feelings help forge collective healing?

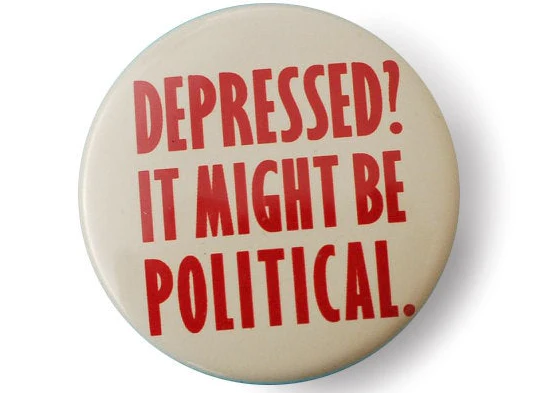

On the 1st of May 2003, five women walked to Chicago’s government office wearing bathrobes. They were preparing for a demonstration; the first ‘Day of the Politically Depressed’. Onlookers began drifting toward the women, who were outnumbered by police in riot gear. An hour later, artist Vanalyne Green arrived in a taxi with a box of white T-shirts that read: “Depressed? It might be political!" Vanalyne is a founding member of Feel Tank, a collective project formed by women in response to their feelings of hopelessness about life in America. “We experience that as an individual feeling, but in fact, there's something quite political about it," Debbie Gould had told one of the curious police officers. The demonstration was light-hearted, but the message clear: “Instead of becoming apathetic, we should politicize our depression."

Almost ten years after that demonstration on a drizzly day in Chicago, Ann Cvetkovich - a queer and Jewish gender studies professor - urged us to think about depression as a cultural and social phenomenon rather than a medical disease in her memoir-cum-critical-essay Depression: A public feeling. In opposition to the prevailing Western belief that mental illness is caused by a biochemical imbalance that can be corrected with medication, Cvetkovich positions depression as a rational reaction to stressors of an unstable and isolating neo-liberal, capitalist society.

We can see this reflected in the fact that common mental health diagnoses are more rampant and severe in the industrialised world, specifically in the United States. If mental illness was rooted in biological causes, why would rates vary widely from country to country, as well as across class systems? In her memoir, Cvetkovich talks of how working in academia was killing her, breeding the fear that nothing she had to say was “important enough or smart enough.” These feelings mirror symptoms associated with clinical depression.

She could have started taking Prozac, like the one in every ten Americans that do, but she turned her attention to the social forces surrounding her depression. She felt that to have ambitions within a society that tells us we are only worth what we produce is to fall victim to an unequal system designed to keep us despondent. “To feel that your work doesn’t matter is to feel dead inside,” she notes. What we call depression, Cvetkovich argues, is “a category that . . . medicalizes the affects associated with keeping up with corporate culture and the market economy.” In other words, depression is to be expected.

Both Cvetkovich and Feel Tank are attempting to de-pathlogize the negative feelings that are associated with depression to turn them into “a possible resource for political action rather than as its antithesis.” The process of regarding depression as a behavioural condition does not mean to understate how devastating depression can be or to deny that treatments can and do work. As Cvetkovich says, “political depression has the simple aim of revealing the social nature of our despair, so we can embrace rather than gloss over bad feelings.”

This tangled link between social issues and psychological has, then, become increasingly to the fore following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. The day after Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced a UK lockdown, university researchers found that there was a 22% increase in people reporting significant depression. People became more mentally resilient as the shock of lockdown settled, but the impact on our mental health hasn’t passed - as evidenced by the uptick in mental health charities dedicating chatbots and forums to Coronavirus anxieties. We are, to put it bluntly, blind to the trauma that will reverberate across the globe in the coming weeks, months and years.

A global pandemic sends out shockwaves of anxiety and fear. From the Great Depression to World Wars, natural disasters and the tragedy of 9/11, global events don’t just collapse the economy, they alter the psychology of nations. At the time of writing, over 7,000 people in the UK have died as a result of coronavirus. Worldwide, over 90,000 people have lost their lives. The virus morphed from distant disease to a rapidly evolving threat to life with a ferocity that quickly rendered the idea of tackling it with a British stiff upper lip futile and ugly. Pre-lockdown, it was the uncertainty that made us anxious. Now, it is the reality - that of drastic changes in routine, a year of cancelled plans, of social isolation, hunger, poverty, domestic abuse, overwhelmed health systems, scams, death, despair and palpable economic devastation - that is making us feel depressed. Framing this depression as social, political and public could help us survive it, to “remind ourselves of the persistence of radical visions.”

Radical visions of a bright future will seem laughable to the thousands of people whose lives have been turned upside down in various ways by the virus. Many people have lost their jobs, and don’t know how they will feed their family. Almost 1 million people applied for Universal Credit in the first two weeks of UK lockdown. Unemployment rates sat at 3.9 per cent before the outbreak. They are forecasted to rise to 5.2 per cent in April. What incremental percentage changes don’t account for are the thousands of people in the UK who are freelance, who work zero-hour contracts or in the gig economy. These people are losing work - and they aren’t going to see the benefits of the government’s pledge to support employers in paying staff.

Whilst rates for depression have been reportedly rising since 1993 across the board, you are at higher risk if you are poor. British epidemiologist Michael Marmot found that ‘children and adults from the lowest 20 percent of households are three times more likely to have common mental health problems than the top 20 per cent’. And about 50 percent of people with debt in the UK have a mental disorder. On a local level, over half of those in the London borough of Islington who claim disability benefits do so for mental ill-health. The ward also has the highest level of child poverty. Scores of psychological health plummeted during the 2007 - 2010 recession - a crisis that is continuing to ‘pose major challenges in the WHO European Region’. A growing body of research shows how social inequality impacts rates of depressive disorders; including correlations between a country’s wealth and the risk of a mood disorder.

The people hit hardest by this crisis are the most vulnerable, and it is these same people who are most likely to experience mental health issues. These two facts are not coincidental. The charity Stonewall found that over half of LGBT+ people experienced depression in 2017; numbers that are reflected across the board. BAME communities are more likely to experience mental health issues than their white peers and are at a higher risk of dying as a result. Statistics from Race for Health show that young Asian women are more than twice as likely to commit suicide as young white women, and young black men are six times more likely than young white men to be sectioned under the Mental Health Act. If you are poor, bisexual, disabled or BAME you are also less likely to benefit from IAPT treatments than those who aren’t. Such racial and economic inequality has been amplified under Covid-19. Statistics show that you are more likely to die from the virus if you are African American. Black people make up 30% of the population of Chicago but account for more than 70% of deaths. The picture is the same across the US and also here in the UK, where a study of more than 2,000 patients critically ill with the virus in England, Wales and Northern Ireland has found that 35% are black, Asian or other ethnic minority. This is more than double the representation in the wider population. The first four doctors who lost their lives as a result of treating Covid-19 patients in the UK were all Muslim men of African or Asian heritage. As Guardian columnist Afua Hirsch put it: “Covid-19 has a way of drawing out the rot in our systems and exposing them. To say coronavirus is a disease that does not discriminate is wishful thinking.” In such conditions, Cvetkovich argues, depression is “a very rational response.”

Yet, if depression is a rational response to social inequalities, pressures and capitalist systems, what can we do about it? As Cvetkovich notes; “Saying that capitalism (or colonialism or racism) is the problem does not help me get up in the morning.” We are currently experiencing devastation caused by widespread, collective pain, but, in the words of Cvetkovich, “feeling bad might, in fact, be the ground for transformation.” On a personal level, experiencing periods of bleakness can give rise to positive change. As Kay Redfield Jamison reflects in her memoir An Unquiet Mind, it is “the individual moments of restlessness, of bleakness . . . that inform one’s life, change the nature and direction of one’s work, and give final meaning and colour to one’s loves and friendships.” Surviving bouts of deep depression will also expose you to the suffering of others. This can either trap you in a pessimistic fear of the world or allow you to be a more sensitive, empathetic person. Literary scholar Jonathan Dollimore echoed this sentiment in his article ‘Depression Studies’, where he observes that: “In periods of depression I’ve certainly had a keener sense of the misery of others.” However: “empathy that derives from the chronic impotence of depression doesn’t add up to much.”

If we consider Cvetkovich’s narrative that depression is like “being stuck” then we need to seek out ways to move. Depression memoirs serve the crucial purpose of personifying the mysteries of depression, but they also position it as something contained within the individual. Individualist ideology means that our emotions suffer as “the state divests itself of responsibility for social welfare and affective life is confined to a privatized family,” says social professor Lisa Duggan.

Lynne Segal advocates for the community as an antidote to individualistic misery in Radical Happiness. The idea of ‘public happiness’ can provide a “route out of the isolation always threatening those experiencing depression”, Segal notes. A route that is unquestionably important now. I myself have felt the power of sharing pain to cultivate hope. I took a connecting flight through China as this outbreak was beginning during which I began talking to the Chinese woman sat next to me with a child sleeping on her lap. She told me of her worry for returning home, and we laughed about me being the only white person on the plane. To mitigate the panic I felt from the incessant pessimism back home, I created a virtual feminine space for positive support. This wasn’t enough to eradicate the deep fear and depression I felt, but, as Cvetkovich reminds us, "there are no magic bullet solutions [for depression].. just the slow steady work of resilient survival, utopian dreaming and other effective tools for transformation." Funding social policies whilst opposing racism, fascism and homophobia is integral to the pursuit for joy in the face of collective anguish.

In attempts to de-pathologize and politicise depression, we must be careful not to undermine the seriousness of such symptoms, or to obfuscate its individualistic manifestation. Instead, this ideology must be used to build an inclusive conversation; one that addresses how we can rebalance psychological inequity. Making depression a community issue can be weaponized by governments to justify cuts to services under the guise of self-help as a magical anecdote, but it also highlights how a social society is a happier one. Sharing imaginings for a more equal, fair future is energising. Soak in the words which Segal uses to end her book: “Happy endings can be joyfully pursued when we feel empowered with others, although as we surely should know by now, such endings can never be said to have finally arrived.”

Sian Bradley is a mental health campaigner and freelance writer who focuses on social issues, technology and what makes us human.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]