The October Revolution of Antoine Volodine

In the centenary of the October revolution, much has been said about it as a moment in history. Here McKenzie Wark inquires as to what becomes of the myth of October, now that we are in the time of the Anthropocene.

“Who will speak of the life we lived in the civilization of the just, how we bolstered and defended it until it was nothing but ruins?” – Ioulghaï Thotaï

To even imagine the October Revolution of 1917, let alone approaching its historical contours, calls for an accounting of its persistence as a myth. Before one can say what happened, one has to see what’s been made of what happened in the mythic narratives of modernity itself.

In many versions of the myth it appears as a tragic or monstrous anomaly on the road to liberal capitalism. As in the Russian joke that socialism is a transitional phase between capitalism and capitalism. Note here that the joke is an inversion of the official Soviet myth, in which socialism is a transitional phase between capitalism and communism. Even those versions of the myth for which it is a bad object have to account for the new myths the event called into being.

The myth of October made the ruling class afraid of us. That the working class might seize power, might abolish the exploitation of man by man and make the whole of nature a common property to be exploited for the benefit of all, for use not exchange — that was a powerful modern myth. Of which the event of October appeared as the miraculous proof. That many wanted to believe it for so long ought not to be surprising. And contrary to a certain cold war demonology, those who really need to be questioned are the ones who were never tempted to believe.

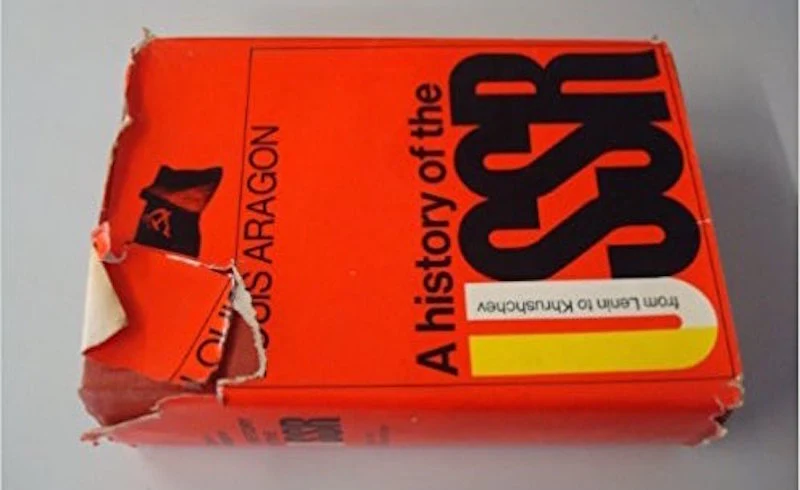

The myth took a mighty blow with Khrushchev’s "revelation" of the crimes of Stalin. Of course many had lost their faith before then, but now it was official. After 1956 true believers had to content themselves with versions of the myth in which Stalin was either a singular anomaly, or for the ultra-tankies, a necessary evil. He was either a detour or a rocky road but the destination remained the same. Contrary to what all other versions of the myth hold, the official ones did not universally produce bad writing. Louis Aragon’s A History of the USSR is, from a strictly literary point of view, quite fine, even if it is just the Khrushchev version of the myth.

Not all of the labor movement, and indeed not all Marxists, accepted the legitimacy of the October revolution. These counter-myths came in left and right variants. October was either a forcing of a moment that was premature, or it was a revolution that did not go far enough. In both, the fatal flaw existed from the beginning. For the democratic socialist, it abandoned due process; for the council communist, it retained too much of the authoritarian party form. Debord’s theory of the spectacle, for instance, is of the second kind.

For those whose version of the myth accepts it as a real and true revolution, but who nevertheless cannot accept Stalin as a necessity or mere aberration, what results is an obsessive search for the means and moment of betrayal. These versions of the myth share with pro-Soviet ones the legitimacy of Lenin and Leninism that both parliamentary socialists and council communists reject. Indeed, they claim to be more true to the mythic stature of Lenin as Marx’s true heir. Stalin is the false heir who displaces the true one.

The true heir could be Bukharin. In Sukhanov’s amazing memoirs of the February revolution the true heir of Marx is Martov (a line I take from Harrison Fluss), but he is a Hamlet-like figure who cannot act. In Victor Serge, the October revolution is legitimate, but the problem is that the heirs of Marx collectively fail him in their struggle against Stalin. His Case of Comrade Tulayev is a masterpiece among this variant of the myth. But the true heir is usually Trotsky. For the Trotskyists, the official Marxism of the Soviet Union ceases to be orthodox and faithful to Lenin. They are the true inheritors and custodians of orthodoxy, in exile and absentia. This is a mythic tradition only validated by the murder of Trotsky by Soviet agents.

It is this variant of the myth that made of the Trotskyists some of the most careful and relentless historians of the Russian revolution and of the Soviet Union, starting with Trotsky himself and continuing with Victor Serge, Boris Souvarine, Isaac Deutscher and so many others. It does not vitiate the historical scholarship to insist that it is animated by a myth, as all historical narratives are necessarily also mythic. But the myth in question is a variant on a structural set of myths, and while Trotskyist historiography questions the viability of other versions of the myth, it rarely questions its own, and even more rarely gets to the question of the structure underlying all the variants of the myth itself.

This is why, in Molecular Red, I decided to stay close to a version of the event that was alive to its mythic dimension — the novels of Andrey Platonov, which I chose to read (as Lukacs might) as historical novels, but also as fictions of the material reality of the myth itself (as Shklovsky might). Like Serge, Platonov was a witness to significant events in Soviet history, but in the countryside more than the city. One of the things going on in Chevengur and Foundation Pit is a kind of peasant ethnography.

These books are sometimes read as satire, but I think they are far from that. Platonov does not write history from the below so much as from below the below. His characters are barely even proletarian. They are homeless, orphans, they do not even have kin. Many are illiterate. Even those that are seem to garble the official dialectical language of party and state, but in so doing construct myths to live by.

One character observes in Chevengur that the Bolsheviks have abolished earth and sky and left peasants with nothing but the horizon. They have taken away both God and private property, and offered the future in its place, shifting the whole axis of mythic existence from the vertical to the horizontal, from an eternal present to a future that is always to-come, from a tangible to an abstract nature. Platonov’s characters lack divine souls, but still struggle to produce a "soul" as a surplus over and above material existence, but which always tends away from the solidarity of absolute poverty.

In the myth of the revolution betrayed, there are many variants as to the moment of betrayal. For Platonov it is the New Economic Policy. The return of market-based transactions and the display cases of consumer goods signals defeat. It is a structure of feeling Platonov probably shared with not a few of those who were mobilized by the civil war and retained a sense of it as a mobilization of a fraternity of egalitarian revolutionaries. There’s a moving portrait in Boris Pilniak's Mahogany and Other Stories of just such a group, living together in a cave and surviving on casual manual labor after their glorious time has passed.

What makes Platonov a problematic figure for those who would hoist him up as an exemplary "dissident" and anti-Soviet writer is that he remained loyal to the myth of revolution and in solidarity with the tenet of proletarian equality to the end. But communism is poverty in Platonov, on the border where life just barely exists. It is a sharing of poverty rather than wealth. Only those who share the same dangers can be comrades. The sheer disorganizing materiality of the world wears away at life and labor, shredding the myth to tatters, and yet it endures.

Whether intentionally or not, Platonov shares a variant of the myth of revolution with Alexander Bogdanov. For both of them, the abolition of capital by labor does not in itself free labor from the constraints of necessity. Nature is for both of them an even deeper problem. The negation of capital by labor is not an affirmation of labor’s productive powers and its command of nature for the material benefit of all. In Bogdanov's Red Star, labor still has to struggle in and against nature for a very long time, and the collective labor of even a socialist society could destroy natural conditions of existence.

Bogdanov had been expelled from the Bolsheviks years before the October revolution, and had an ambivalent status as an old Bolshevik who neither turned against the revolution nor endorsed it. He retreated into education and scientific work in the natural sciences. Platonov had been swept up in active struggle in the civil war period, but turned away from writing and worked on practical questions. He had a familiarity with the railways, hydrology and electrical engineering and worked outside the urban centers on many of these problems. In very different ways they remained loyal to the myth of revolution, if not quite to what the October revolution became, but were always dissenters from the myth of a release of the productive power of nature into the hands of the proletariat.

This is nowhere clearer than in Platonov’s Foundation Pit, in which workers dig and dig and dig deeper the foundations for a House of the Proletariat that is never to be. They lack the material means to create a base that would sustain and support the gleaming superstructure imagined in Bolshevik mythology. The act of collective digging wears the proletariat out, and leads to the death of the orphan child who was the hope projected over the horizon into the future. She is buried in a little coffin in the pit itself. As Bogdanov had foreseen. Even after the negation of capital, labor has no relation, in and against nature, bestowed upon it which could sustain it. These seem to me the variants of the myth from which to begin again.

Labor did not defeat capital. If anything, history turned as much on intra-ruling class struggles. The ruling class of our time controls the value chain not by owning land or factory, but by controlling information. The old owners of the means of production are subordinated to those who own the vector of information. If anything this is worse for labor than exploitation by capital was. This mode of production, whatever it now is, no longer has the choke points at which labor could press its particular powers into general service, as it did in October. You can’t shut it down by seizing the railways, or shutting down the mines or the ports. It just routes around labor’s material power.

The promise of labor’s victory over capital, which the myth of October seemed to hold out as real, was in any case no solution to labor’s struggle in and against nature. The Soviet command economy still persisted with a value form that undermined in the long run its own material conditions of existence, as did that of capitalism. Tarkovsky’s film Stalker vividly pictures the landscape that resulted, with its abandoned battlefields and industrial installations. It seems unlikely that he would have read much Platonov, but the abandoned hydrological works that are the last setting in the film could be straight out of Platonov’s mythic imagination.

This might seem like a rather long set-up to get to the fiction of Antoine Volodine, even if it is still the barest sketch of the modern mythic narrative and landscape in which October figures. But I want to suggest that Volodine is one of the few writers who has picked up where Platonov leaves off. And he does it not by producing a variant of the myth or even an analysis of the mythic form itself, but by proposing a modification in the way myth works in the world.

Here we have to put on the table some of the literary peculiarities of this work. These are well-known to people with an interest in Volodine, but can perhaps be understood now in a new light. Antoine Volodine is one of a series of heteronyms used by a writer who is otherwise nameless. There are books published in the name of Volodine, but also Lutz Bassman, Manuela Draeger, Elli Kronauer and short texts or narracts in many names, including Ioulghaï Thotaï. Kronauer appears as a character in the Voldine novel on which I’ll focus shortly, and this is not uncommon in his work. All of the works belong to an imaginary movement of post-exotic writing, of which there is a manifesto published by the Volidine heteronym: Post-Exoticism in Ten Lessons, Lesson Eleven (Open Letter, 2015).

Not much is public about the author of this body of work, other than that he writes in French and has taught Russian and translates works from that language, including work by the Strugatsky brothers — authors of novel Stalker, on which the Tarkovsky film is loosely based. The additional conceit connecting all of the heteronyms is that they are all political prisoners confined to their cells in some maybe-future, maybe-imaginary other world. Post-exotic writing is writing from prison, in both a political and existential sense. And where prison is, as Manuela Draeger says, a “lesser hell.”

Volodine’s Radiant Terminus (Open Letter, 2017) seems on one level to be something of a science fiction novel. It is set in the Russian taiga. Like the far east of Platonov’s Soul it is something of a mythic landscape. It is set after the collapse of the second Soviet Union. Its characters are like Platonov’s in Chevengur, wandering about, trying to fight a civil war where the enemy is absent, but the odds are still against them. They ride the railways, get lost in the forest, come across a collective farm and a labor camp, apparently in the middle of nowhere, cut off from the world yet still functioning. Their existence is not so much one of survival as "sousvival." (284)

There is no sky and no land. Fog and snow shroud them. The horizon is gone too, replaced by a barbed-wire fence. The mythic structure of the revolution has dissolved into indifference. This might be what post-exotic literature is. Some critics treat it as a nonsense name for a fake avant-garde, but I think it is meant to signal there is no binary term, no outside, no other against which individuation might predicate itself. The characters are barely people, barely even alive. They wander about in the bardo, in the state between the death of the body and that of the soul. They are undead.

The first place of encounter is the collective farm, which in Platonov’s Foundation Pit is the locus of an obscene and literal liquidation of the kulaks. In Radiant Terminus, the foundation pit becomes instead a nuclear reactor that has failed and melted down two kilometers into the earth. The whole second Soviet Union had relied on this distributed nuclear power and it has all failed, and yet the collective farm still draws power from it, and the undead comrades who populate it have become immune to its radiation.

Over the collective farm presides a monstrous shamanic figure, a kulak with an axe in his belt from Russian folk stories, but also a Stalin figure, constantly broadcasting his monologs over the loud speakers. As in Platonov, the characters who inhabit this landscape are mostly men, and one of their principle problems is whether women can belong to the fraternity of absolute equality. The despot of the collective farm can only recognize women as daughters or wives, or occasionally both — again, there’s no difference. His is an incestuous power. He invades their bodies and dreams.

This despot at the heart of the text is of course also the writer. Writers invade the bodies and dreams of their characters. The fictionalizing of the author function through heteronyms is partly a response to this, even if it just lengthens the chain of mythic levels, leaving the author hidden and nameless behind this landscape of the imaginary. One thing Radiant Terminus raises as a problem is whether those myths of October that wanted to abolish the despot from the myth — that want the myth without Stalin — retain in his stead the despotism of the author within the text. There’s a will to power in the myth of October betrayed that installs the author in the despot’s place. Of course a despot in a text is far, far less of a problem than an actual one, but it points to an enduring problem with authorship in all its forms.

The figure that shows the (patriarchal) despot of the writer at work is that of the woman as character. Platonov broached this problem in Chevengur when the women arrive at the imaginary almost-utopia of Chevegur. Then men immediately want to make them comades. They want the women to be their sisters. But the women are no fools. They expect to be daughter-wives: exploited, abused, refused equality. Volodine proposes the solution that Platonov cannot: a terrible and furious revolt, one that destroys all difference.

The other imaginary locus in the text is the labor camp. There’s a train full of soldiers and detainees that seems perennially in route to the camp. It is no longer clear who is a solider and who is a detainee. They switch positions. They are already neither dead nor living so it hardly matters. The camp for which they seek is what is at the horizon. It is the place that has abolished the possibility of anything else. The camp is truly post-exotic. It is what is at the end of history, or rather, at the end of the mythic terrain any possible history can inhabit.

How is this post-exotic landscape not a reactionary solution to the failure of the October revolution? Like the revolutionaries of Platonov’s world, those of Volodine’s never give up on solidarity with absolute equality. This is what keeps them, if not alive, then undead, in the world at the end of history, in a world become universal labor camp. If one cannot will any difference, any change, then will this abolition of difference, which makes not only everyone but everything absolutely equal. For it is better to will the abolition of difference than to not will. Even if, actually, the will to abolish difference extinguishes the will. Because even with the will extinguished, when everything is an indifferent dreamlike state, neither real nor surreal nor hyperreal nor unreal, there’s not nothing. There’s something. There’s writing, in which everything is actually equal — and equally actual.

If there is still writing, then there’s still existence, or at least its inky shadows. Even when there’s no longer any difference between dream and non-dream. The post-exotic text is not surrealist, in that the mythic is not a supplementary reality. Nor is it hyperreal. Baudrillard becomes a little old fashioned in his insistence on a difference, in wanting the hyperreal to be more real. The post-exotic lacks a distinction between dream and something else. No term is exotic to another.

The author behind the Voldine texts has said that he wants the books to invade their reader’s dreams, a suggestion that works on many of his readers. It certainly worked on me. I dreamt that I was the author of the author. I dreamt I had fabulated him, and that he had made up Voldine and the other heteronyms, but that I in turn was a character created by one of the heteronyms, but I did not know which one. Or maybe the heteronym who had dreamt me into existence had not written yet. It was a disturbing dream, particularly as I am a reader of Volodine and as such I know that his characters are neither alive nor not alive. So it was a dream in which I did not cease to exist and yet was not exactly existing.

Like any author worth reading, Volodine calls into existence more than one kind of reader. I read Volodine, and indeed the author of Volodine, as wanting to remain in solidarity with an element of the myth of October: the instantiation in the world of the possibility of equality. The dead who remained in solidarity with the principle of equality are still (almost) alive. In their graves, in their prisons, in their texts. They are witnesses to the myth of October before absent masses.

But they write in frank acknowledgement of defeat. Even the second Soviet Union is defeated. And there will not be a third: the blasted, ruined nature within which characters wander is not a nature that could be the means of overcoming collective necessity again for millennia to come. Probably not intentionally, but still: this is a myth of the Anthropocene.

If we are only comrades if we all face the same dangers, then perhaps the Anthropocene is, in principle, a time that could be a time of the comrade. I don’t want to give too much away about what happens in Radiant Terminus, but if it’s the woman who destroys the despotic order of the collective farm, what happens at the labor camp is something else. Our prisoners and guards — it is a matter of indifference which is which — find the camp, but it won’t let them in. I can’t help thinking of climate refugees, fleeing disaster, war and civil collapse, confronting the walls of the over-developed world which won’t let them in. But where flood and fire are finding their way in anyway.

The decision for equality in Volodine reminds me a little of Alain Badiou, but not quite. For Badiou, Lenin’s fidelity to Marx, his decision for communism as radical equality, is the decision that makes him a subject in the world. But in Volodine, as in Platonov, equality is not a matter of the subject. In Platonov, it’s a matter of bare existence; in Volodine, it’s a matter of bare non-existence.

The myth of communism as equality is not the only variant, however. Here it may help to split the myth into its two components, into the duality within the mythic structure that particular myths seek to overcome through the playing out of variants. Is equality a matter of bodies or souls? Is it symbolic or material equality? Communism’s critique of liberalism is that it stops short at symbolic equality. Rather, equality should be both symbolic and material. However, there was another path. As I tried to show in The Spectacle of Disintegration, Charles Fourier chose instead to invert the myth of liberal, symbolic equality. Communism could mean material equality, but symbolic difference. In Fourier’s utopia, no one is compelled to sacrifice their labor for another. Nobody lives with less of their material needs satisfied than another. Nobody even lives with less of their desires met. And yet there is difference, even ranking, at the symbolic level.

Contrary to the liberal myth about utopia, in which it is fair to say some versions of communism do participate, utopia need not be an abstract, "heavenly" or future ideal brought into the present in imaginary form. It need not be from over the horizon. It can be a working-through of necessity in an uncompromising manner, a pressure on myth from below, even from below the below, from base matter. While their attitudes as to what the consequences of this are for myth are very different, as writers, Fourier, Platonov, and Volodine all work this territory relentlessly. The problem of materiality becomes a problem of the materiality of language, which works its way into and against myth as received ideas and structures of feeling.

What saves them from becoming reactionary writers is that in the absence of a myth of a better world, they are not writers of a perennial state of total war. They are writers neither pacific nor war-like, but of a specific situation, a moment of defeat. For Fourier, the defeat of anything positive in the French Revolution; for Platonov, the defeat of the October Revolution; for Volodine, the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the extinction of any chance of its redemption. One thinks here of the moment of Gorbachev and the last dim hope that something could be reconstructed, that there could be light shining on the ruins.

Thinking the moment of defeat is something that is common to certain strands of Marxism but not others. The post-1956 exodus from the party — the real party — is saturated in this thinking of defeat and the need to start again, to question the myths, to work the fabric of the mythic differently. It is a different sensibility to those who thought the spirit of October lived on somewhere. That its legitimate heirs went on exile. That the one true revolutionary movement could escape into the world of sects and texts — and preserve its essence.

The Anthropocene confronts us with the possibility that all our myths are at an end. Not just the Marxist myth of modernity, but the liberal ones as well. And one must say: also the reactionary ones. The revival of reactionary myth seems to be worldwide, and to be combated in both its popular and its more intellectual appearances. The Gods will not save us.

One of the virtues of thinking through the moment of defeat, specifically for the labor movement, and within the labor movement for Marxists, is that it renders obsolete the old feuds between its factions, all of which played out variants of the same myth. The communists, the socialists, the anarchists, the parliamentary-roaders, the Leninists, the Trotskyists, the Maoists, the Bukharinites, the council communists, the spontaneous-insurrectionists, the Euro-communists, the third-worlders — its defeat for all of us. The rhetorical form of preserving the true version by critiquing the false ones has collapsed along with the myth itself.

This then becomes a moment when the aesthetic appears as a primary rather than secondary concern. How to perceive the world, how to narrate the world — these become unavoidable problems. Literature is no longer beholden to theory. There’s an obligatory equality of forms of intellectual work in the moment of defeat. We are all just general intellects confronted by a totality of problems outside the specific mythic variants within which we labor. The claims to sovereignty, to having the form of knowing or perceiving that trumps all the others now appear especially pathetic and suspect. We all face the same dangers. All our ways of knowing are prima facie equal. We can only proceed if we acknowledge defeat and act as comrades.

Marx said in the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon that all the events of world history appear twice, first as tragedy, then as farce. As to what happens the third time, he was silent. The "October Revolution of Antoine Volodine" may have an answer to that, in his mythic landscape where a second Soviet Union has risen and fallen, leaving its character adrift in a third kind of time. What one does the third time is not grasp history as variations in different genres of the same myth. One perceives the possibility of the end of that myth. Perhaps we will not, as Marx had hoped, at last confront our real relations with our kind. But perhaps we can discover within the space of the existing myth the constitutive indifference to which its terms have been reduced. And make a more useful one. The space and time of indifference is that from which all myth issues, and that it then calls into existence as its condition of existence.