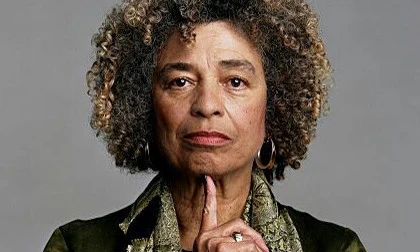

Angela Davis: An Interview on the Futures of Black Radicalism

"The concept associated with Black Marxism that I find most productive and most potentially transformative is the concept of racial capitalism.... Global capitalism cannot be adequately comprehended if the racial dimension of capitalism is ignored."

Futures of Black Radicalism brings together key activists, scholars and thinkers of the Black Radical Tradition in recognition and celebration of the work of Cedric J. Robinson, who first defined the term. The essays collected here look at the past, present and future of Black radicalism, as well as the influences it has had on other social movements. Racial capitalism, another powerful idea developed by Cedric J. Robinson, links to international social movements of today, expoloring the links between Black resistance and anti-capitalism. Here we share an interview with Angela Davis by Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin.

In your scholarship you have focused on prison abolitionism, Black feminism, popular culture and the blues, and Black internationalism with a focus on Palestine. Taken together, how does this work draw inspiration from, and perhaps move forward, the Black Radical Tradition?

Cedric Robinson challenged us to think about the role of Black radical theorists and activists in shaping social and cultural histories that inspire us to link our ideas and our political practices to deep critiques of racial capitalism. I am glad that he lived long enough to get a sense of how younger generations of scholars and activists have begun to take up his notion of a Black Radical Tradition. In Black Marxism, he developed an important genealogy that pivoted around the work of C. L. R. James, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Richard Wright. If one looks at his work as a whole, including Black Movements in America and e Anthropology of Marxism, as H. L. T. Quan has pointed out, we cannot fail to apprehend how central women have been to the forging of a Black Radical Tradition. Quan writes that when asked about why there is such an enormous focus on the role of women and resistance in his body of work, Robinson replies, “Why not? All resistance, in effect, manifests in gender, manifests as gender. Gender is indeed both a language of oppression [and] a language of resistance.”

I have learned a great deal from Cedric Robinson regarding the uses of history: ways of theorizing history—or allowing it to theorize itself—that are crucial to our understanding of the present and to our ability to collectively envisage a more habitable future. Cedric has argued that his remarkable excavations of history emanate from the positing of political objectives in the present. I have felt a kinship with his approach since I first read Black Marxism. My first published article—written while I was in jail—which focused on Black women and slavery was, in fact, an effort to refute the damaging, yet increasingly popular, discourse of the Black matriarchy, as represented through official government reports as well as through generalized masculinist ideas (such as the necessity of gender-based leadership hierarchies designed to guarantee Black male dominance) circulating within the Black movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Although this is not how I was thinking about my work at that time, I certainly would not hesitate today to link that research to the effort to make a Black radical, thus feminist, tradition more visible.

The new field formation—critical prison studies and its explicitly abolitionist framework—situates itself within the Black Radical Tradition, both through its acknowledged genealogical relation to the period in US history we refer to as Radical Reconstruction and, of course, through its relation both to the work of W. E. B. Du Bois and to historical Black feminism. The work of Sarah Haley, Kelly Lytle Hernandez, and an exciting new generation of scholars, by linking their valuable research with their principled activism, is helping to revitalize the Black Radical Tradition.

With every generation of antiracist activism, it seems, narrow Black nationalism returns phoenix-like to claim our movements’ allegiance. Cedric’s work was inspired, in part, by his desire to respond to the narrow Black nationalism of the era of his (and my) youth. It is, of course, extremely frustrating to witness the resurgence of modes of nationalism that are not only counterproductive, but contravene what should be our goal: Black, and thus human, flourishing. At the same time it is thoroughly exciting to witness the ways new youth formations— Black Lives Matter, BYP100, the Dream Defenders—are helping to shape a new Black feminist-inflected internationalism that highlights the value of queer theories and practices.

What is your assessment of the Black Lives Matter movement, particularly in light of your participation in the Black Panther Party during the 1970s? Does Black Lives Matter, in your view, have a sufficient analysis and theory of freedom? Do you see any similarities between the BPP and BLM movement?

As we consider the relation between the Black Panther Party and the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement, it feels like the decades and generations that separate one from the other create a certain incommensurability that is a consequence of all the economic, political, cultural, and technological changes that make this contemporary moment so different in many important respects from the late 1960s. But perhaps we should seek connections between the two movements that are revealed not so much in the similarities, but rather in their radical differences.

The BPP emerged as a response to the police occupation of Oakland, California, and Black urban communities across the country. It was an absolutely brilliant move on the part of Huey Newton and Bobby Seale to patrol the neighborhood with guns and law books, in other words, to “police the police.” At the same time this strategy—admittedly also inspired by the emergence of guerrilla struggles in Cuba, liberation armies in southern Africa and the Middle East, and the successful resistance offered by the National Liberation Front in Vietnam—in retrospect, reflected a failure to recognize, as Audre Lorde put it, that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” In other words, the use of guns—even though primarily as symbols of resistance—conveyed the message that the police could be challenged effectively by relying on explicit policing strategies.

A hashtag developed by Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi in the aftermath of the vigilante killing of Trayvon Martin, #BlackLivesMatter began to transform into a network as a direct response to the rising protests in Ferguson, Missouri, which manifested a collective desire to demand justice for Mike Brown and for all of the Black lives sacrificed on the altar of racist police terror. In asking us to radically resist the racist violence at the very heart of policing structures and strategies, Black Lives Matter early on recognized that we would have to place the demand to demilitarize the police at the center of our e orts to move toward a more critical and more collective mode of justice. Ultimately linked to an approach that calls for the abolition of policing as we know and experience it, demilitarization also contested the way in which police strategies have been transnationalized within circuits that link small US police departments to Israel, which dominates the arena of militarized policing associated with the occupation of Palestine.

I appreciate the more complicated analysis that is embraced by many BLM activists, because it precisely reflects a historical-mindedness that is able to build upon, embrace, and radically critique activisms and antiracist theories of the past. As the BPP attempted—sometimes unsuccessfully—to embrace emergent feminisms and what was then referred to as the gay liberation movement, BLM leader and activists have developed approaches that more productively take up feminist and queer theories and practices. But theories of freedom are always tentative. I have learned from Cedric Robinson that any theory or political strategy that pretends to possess a total theory of freedom, or one that can be categorically understood, has failed to account for the multiplicity of possibilities, which can, perhaps, only be evocatively represented in the realm of culture.

Your most recent scholarship is focused on the question of Palestine, and its connection to the Black freedom movement. When did this connection become obvious to you and what circumstances, or conjunctures, made this insight possible?

Actually my most recent collection of lectures and interviews reflects an increasingly popular understanding of the need for an internationalist framework within which the ongoing work to dismantle structures of racism, heteropatriarchy, and economic injustice inside the United States can become more enduring and more meaningful. In my own political history, Palestine has always occupied a pivotal place, precisely because of the similarities between Israel and the United States—their foundational settler colonialism and their ethnic cleansing processes with respect to indigenous people, their systems of segregation, their use of legal systems to enact systematic repression, and so forth. I often point out that my consciousness of the predicament of Palestine dates back to my undergraduate years at Brandeis University, which was founded in the same year as the State of Israel. Moreover, during my own incarceration, I received support from Palestinian political prisoners as well as from Israeli attorneys defending Palestinians.

In 1973, when I attended the World Festival of Youth and Students in Berlin (in the German Democratic Republic), I had the opportunity to meet Yasir Arafat, who always acknowledged the kinship of the Palestinian struggle and the Black freedom struggle in the United States, and who, like Che, Fidel, Patrice Lumumba, and Amilcar Cabral, was a revered figure within the movement for Black liberation. This was a time when communist internationalism—in Africa, the Middle East, Europe, Asia, Australia, South America, and the Caribbean—was a powerful force. If I might speak about my own story, it would have almost certainly led to a different conclusion had not this internationalism played such a pivotal role.

The encounters between Black liberation struggles in the United States and movements against the Israeli occupation of Palestine have a very long history. Alex Lubin’s Geographies of Liberation: The Making of an Afro-Arab Political Imaginary attempts to chart important aspects of this history. Oftentimes, however, it is not in the explicitly political realm that one discovers moments of contact. As Cedric Robinson emphasized, it is in the cultural realm. Of course Robin Kelley’s Freedom Dreams: The Making of the Black Radical Imagination accentuates the arena of surrealism as an especially generative contact zone. In the latter twentieth century, it was Black feminist poet June Jordan who pushed the issue of the occupation of Palestine to the fore. Despite the Zionist attacks she suffered, and despite the temporary loss of a very important friendship with Adrienne Rich (who later also became a critic of the occupation), June became a powerful witness for Palestine. In her poetry she felt impelled to embody the juncture of Black and Palestine liberation. “I was born a Black woman / and now / I am become a Palestinian / against the relentless laughter of evil / there is less and less living room / and where are my loved ones / It is time to make our way home.” At a time when feminists of color were attempting to fashion strategies of what we now refer to as intersectionality, June, who represents the best of the Black Radical Tradition, taught us about the capacity of political affinities across national, cultural, and supposedly racial boundaries to help us imagine more habitable futures. I miss her deeply and am so sorry that she did not live long enough to experience Black Lives Matter activists across this continent raising banners of resistance to the occupation of Palestine.

As I have remarked on many occasions, when I joined a delegation in 2011 of indigenous and women of color feminist scholar activists to the West Bank and East Jerusalem, I was under the impression that I thoroughly understood the occupation. Although all of us were already linked, to one extent or another, to the solidarity movement, we were all thoroughly shocked by how little we really knew about the quotidian violence of the occupation. At the conclusion of our visit, we collectively decided to devote our energies to participating in BDS and to help elevate the consciousness of our various constituencies with respect to the US role—over $8 million—in sustaining the military occupation. So I remain deeply connected in this project to Chandra Mohanty, Beverly Guy-She all, Barbara Ransby, Gina Dent, and the other members of the delegation.

In the five years following our trip, many other delegations of academics and activists have visited Palestine and have helped to accelerate, broaden, and intensify the Palestine solidarity movement. As the architects of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement have modeled their work on the anti-apartheid campaign against South Africa, US activists have attempted to point out that there are profound lessons to be gleaned from earlier boycott politics. Many organizations and movements within the United States have considered how the incorporation of anti-apartheid strategies into their agendas would radically transform their own work. Not only did the anti-apartheid campaign help to strengthen international efforts to take down the apartheid state, it also revived and enriched many domestic movements against racism, misogyny, and economic justice.

In the same way, solidarity with Palestine has the potential to further transform and render more capacious the political consciousness of our contemporary movements. BLM activists and others associated with this very important historical moment of a surging collective consciousness calling for recognition of the persisting structures of racism can play an important role in compelling other areas of social justice activism to take up the cause of Palestine solidarity—specifically the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement. Alliances on university campuses that bring together Black student organizations, Students for Justice in Palestine, and campus chapters of Jewish Voice for Peace are reminding us of the profound need to unite antiracist efforts with strong challenges to Islamophobia and anti-Semitism, and with the global resistance to the apartheid policies and practices of the State of Israel.

Theoretically and ideologically, Palestine has also helped us to broaden our vision of abolition, which we have characterized in this era as the abolition of imprisonment and policing. The experience of Palestine pushes us to revisit concepts such as “the prison nation” or “the carceral state” in order to seriously understand the quotidian carceralities of the occupation and the ubiquitous policing by not only Israeli forces but also the Palestinian Authority. This, in turn, has stimulated other research directions on the uses of incarceration and its role, for example, in perpetrating notions of a permanent binarism with respect to gender and in naturalizing segregation based on physical, mental, and intellectual ability.

What sort of social movements can, or should, exist at the present conjuncture, given the ascendance of American global hegemony, neoliberal economic relations, militarized counterinsurgency at home, and racial “color blindness”?

At a time when popular discourse is rapidly shifting as a direct response to pressures emanating from sustained protests against state violence, and from representational practices linked to new technologies of communication, I suggest that we need movements that pay as much attention to popular political education as they pay to the mobilizations that have succeeded in placing police violence and mass incarceration on the national political agenda. What this means, I think, is that we try to forge an analysis of the current conjuncture that draws important lessons from the relatively recent campaigns that have pushed our collective consciousness beyond previous limits. In other words, we need movements that are prepared to resist the inevitable seductions of assimilation. The Occupy campaign enabled us to develop an anti-capitalist vocabulary: the 99 percent versus the 1 percent is a concept that has entered into popular parlance. The question is not only how to preserve this vocabulary—as, for example, in the analysis offered by the Bernie Sanders platform leading up to the selection of the 2016 Democratic candidate for president—but rather how to build upon this, or complicate it with the idea of racial capitalism, which cannot be so neatly expressed in quantitative terms that assume the homogeneity that always undergirds racism.

Cedric Robinson never stopped excavating ideas, cultural products, and political movements from the past. He attempted to understand why trajectories of assimilation and of resistance in Black freedom movements in the United States co-existed, and his insights—in Black Movements in America, for example—continue to be valuable. Assimilationist strategies that leave intact the circumstances and structures that perpetuate exclusion and marginalization have always been offered as the more reasonable alternative to abolition, which, of course, not only requires resistance and dismantling, but also radical reimaginings and radical reconstructions.

Perhaps this is the time to create the groundwork for a new political party, one that will speak to a far greater number of people than traditional progressive political parties have proved capable of doing. This party would have to be organically linked to the range of radical movements that have emerged in the aftermath of the rise of global capitalism. As I reflect on the value of Cedric Robinson’s work in relation to contemporary radical activism, it seems to me that this party would have to be anchored in the idea of racial capitalism—it would be antiracist, anti-capitalist, feminist, and abolitionist. But most important of all, it would have to acknowledge the priority of movements on the ground, movements that acknowledge the intersectionality of current issues— movements that are sufficiently open to allowing for the future emergence of issues, ideas, and movements that we cannot even begin to imagine today.

Do you make a distinction, in your scholarship and activism, between Marxism and “Black Marxism”?

I have spent most of my life studying Marxist ideas and have identified with groups that have not only embraced Marxist-inspired critiques of the dominant socioeconomic order, but have also struggled to understand the co-constitutive relationship of racism and capitalism. Having especially followed the theories and practices of Black communists and anti-imperialists in the United States, Africa, the Caribbean, and other parts of the world, and having worked inside the Communist Party for a number of years with a Black formation that took the names of Che Guevara and Patrice Lumumba, Marxism, from my perspective, has always been both a method and an object of criticism. Consequently, I don’t necessarily see the terms “Marxism” and “Black Marxism” as oppositional.

I take Cedric Robinson’s arguments in Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition very seriously. If we assume the unquestioned centrality of the West and its economic, philosophical, and cultural development, then the economic modes, intellectual histories, religions, and cultures associated with Africa, Asia, and indigenous peoples will not be acknowledged as significant dimensions of humanity. The very concept of humanity will always conceal an internal, clandestine racialization, forever foreclosing possibilities of racial equality. Needless to say, Marxism is firmly anchored in this tradition of the Enlightenment. Cedric’s brilliant analyses revealed new ways of thinking and acting generated precisely through the encounters between Marxism and Black intellectuals/activists who helped to constitute the Black Radical Tradition.

The concept associated with Black Marxism that I find most productive and most potentially transformative is the concept of racial capitalism. Even though Eric Williams’s Capitalism and Slavery was published in 1944, scholarly efforts exploring this relationship have remained relatively marginal. Hopefully the new research on capitalism and slavery will help to further legitimate the notion of racial capitalism. While it is important to acknowledge the pivotal part slavery played in the historical consolidation of capitalism, more recent developments linked to global capitalism cannot be adequately comprehended if the racial dimension of capitalism is ignored.

The above is excerpted from Futures of Black Radicalism, edited by Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin.