Our Streets

Heather Heyer was killed by a person and not a car, and yet the car, a Dodge Challenger, seems almost an extension of the person.

Heather Heyer wasn’t killed by a car. She was killed by a person, James Alex Fields, who drove at 40 mph into a crowd of antifascist and antiracist protesters, smashed into the vehicle in front of him, then backed up over more people. Cars kill people in the case of accidents but this was purely intentional. Fields appears by all indications to be a particularly zealous, 20-year-old neo-Nazi, remembered by schoolmates and teachers as a Hitler-venerating creep. He killed Heyer and injured dozens of others at the end of a day of protest and counter-protest in which his side, a coalition of neo-Nazis, white nationalists, patriot militias, pro-confederates, and KKK called Unite the Right, had unquestionably lost. They were surrounded on all sides, harried by counter-protesters, and eventually cleared from the rally location by police using teargas. Failure like that breeds desperation. As Fields drove away from the scene of the protest, a wall of people chanting and celebrating their victory blocked his way. So he decided to drive straight through them.

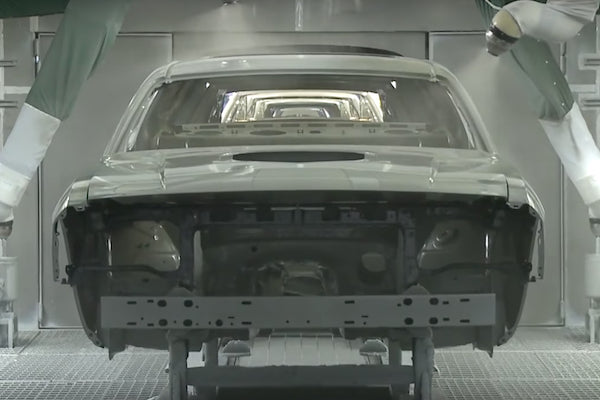

Heather Heyer was killed by a person and not a car, and yet the car, a Dodge Challenger, seems almost an extension of the person. It has a Ram emblem on its hood, after all. Part of the Chrysler family, Dodge has a bad reputation among car industry watchers, who believe it “markets [its] cars to sociopaths.” Ads for the Challenger are adorned with slogans like “Come At Me,” “Ultimate Aggression,” and tellingly “This is America, Drive Like It.” A reboot of a 1970s muscle car, the Challenger was released at the tail end of a series of nostalgic remakes of 60s and 70s models. Throughout the commodity boom of the 2000s, as oil prices rose on the back of the Iraq War, US automakers put out a number of these retro gas guzzlers, flipping the bird at the new century and its rising temperatures. They hearken back not only to a golden age of American automaking but to the prosperity that accompanied it.

In the outskirts of deindustrialized Toledo, where Fields had been living and where Chrysler and its suppliers still operate, Trump campaigned effectively on this backward gaze. He promised to bring back the good industrial jobs that not only built the great American muscle cars of the 1960s and 1970s but provided the decent wages that allowed working-class people to purchase them. He promised to do this through explicitly racist or at least nationalist means: protectionist tariffs against a nefarious China, a wall along the southern border to protect the jobs of citizens from immigrants, and infrastructure programs that would encourage the cultivation of domestic resources, particularly fossil fuels. In doing so, Trump helped to transform the real industrial prosperity that was into the mythic prosperity that was not. To be sure, working-class whites were the main beneficiaries of the industrial boom of the postwar period. Antiracist struggle, however, along with wartime labor shortages, desegregated many factories and opened up good-paying jobs to blacks who had migrated from the south. In some places, white workers opposed these efforts; in others, they were in solidarity with them. The labor market in the postwar boom was much less of a zero-sum game than what has come after it. When employment is expanding there’s much less reason to think that your job comes at the expense of someone else’s unemployment. But once the layoffs began in the 1970s and 1980s, race was very much the decider of who lost and who kept their jobs. Racism paid the bills, even if white workers eventually lost their jobs too when the plants closed entirely. Thus began the seductive mythology of a golden age of whiteness in the minds of young, drifting men like Fields — the fantasy of muscular autoworkers buying back the muscle cars they built and still having enough left over to pay for a mortgage. The Challenger is white revanchism incarnate, the hood jutting forward over the scowling grill like an angry drunk looking for a fight, pushing his head forward, and throwing his arms out to the side.

Unlike the revamps of the Ford Mustang and Chevy Camaro, the Challenger had the misfortune of being released in 2008, just as the economy was collapsing under mountains of bad debt. When those jobs and the wages they paid vanished, plentiful credit appeared to cover the gap. Automakers moved into the financing business; they didn’t just make cars, they made loans, and when the loans stopped so did car sales. In early 2009, if you drove east from Berkeley (where I live) toward Sacramento, you’d come across a massive storage lot, filled with what must have been 10,000 cars, victims of a particularly precipitous drop in demand. They were mostly made by Chrysler, the worst hit of US auto manufacturers and one of the two that had to be bailed out by the government. A friend and I visited one afternoon, amazed at the scale of it. This number of cars is sold in the Bay Area in a good week, but as long as everything is kept in motion no one really notices. It was as if we had pressed pause during a particularly action-packed sequence, distilling some clear image from the blur. The image finds its way into a poem he wrote

ten thousand cars

paratactically abandoned

ten thousand Sebring Sedans

and Explorers

and Pontiac G8s and in oxide

orange a single Challenger

that last hoplite

of American heavy metal

Fields was a hoplite, too. There is a picture of him holding a shield in a line of other neo-Nazi shield holders, a mini-phalanx, manned not by the citizen-warriors of Ancient Greece or Rome but by young men in white polo shirts and khaki parts. His shield is adorned with crossed fasces, the Roman symbol of authority that Mussolini and the Italian fascists appropriated. In footage of the clashes in Charlottesville, you can see these fascist shields charge at the antifascists, breaking through their line. A few of the shield holders spill into the crowd of antifascists, falling to the ground and getting pummeled. The Confederate and KKK re-enactors among them could probably tell you what Civil War battle this doomed charge resembled, as the fascists and their friends were swept from the park by the police on one side and antifascists on the other. The night before they had marched onto the University of Virginia campus bearing torches and chanting “You will not replace us” and “Jews will not replace us.” But they were replaced that day. Their charge failed. Fields, however, had a Challenger.

I’ve seen cars drive into protest crowds many times. We live in the great age of the protest blockade. The two most powerful social movements of recent years — the series of riots, protests, and blockades later dubbed Black Lives Matter and the protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline in Standing Rock, North Dakota — had the blockade at their center. At the height of the BLM mobilizations, after the non-indictment of the cop who murdered Michael Brown, protesters marched onto freeways in over 70 cities. In Standing Rock, the Lakota and Dakota Sioux working to halt the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline in consort with Native Americans from other tribes and non-native accomplices, shut down roads that gave workers and their machines access to the site where the pipeline would cross the Missouri River.

Angry drivers force their cars through blockades all the time, but they usually do so at 5 or 10 miles per hour, slow enough for people to jump on the car, pound on its windows, or sometimes, if the crowd is especially rowdy, smash the windows out with bats, sticks, and rocks. I’ve seen people swept up on to the hoods of cars. I’ve seen broken legs and injured feet from cars driving into crowds. I’ve also ignored the good advice of everyone and read the comments on news articles about such blockades and noticed the frequency with which commenters promise to run over protesters or shoot them if confronted with such a situation. In January, right before Trump’s inauguration, Fox News ran a video collage of cars driving through protesters (set to Ludacris’ “Move Bitch,” a song I’ve heard chanted as protesters pushed through police lines).

Americans can be imperious about their road rights, as if the freedom to drive one’s car down a stretch of asphalt unimpeded were written into the constitution. In fact, legislators in several states have tried recently to spell out such rights in statute, introducing much harsher penalties for blocking the road but also removing civil liability for drivers who kill blockaders accidentally. In Indiana, a lawmaker introduced a bill requiring police to use “any means necessary” to clear the roadway. Police and police unions are particularly outraged at protest blockades. The police are, as we know, absolute masters of the road. They put on their sirens and their lights and the seas part for them. Someone standing in the road and refusing to move in the face of their command is an intolerable affront to that sovereignty. After the events in Charlottesville, the head of the police union in Santa Fe, New Mexico put up a meme with the words “All Lives Splatter” and a picture of stick figures being run over by a Jeep. A cop in Springfield, IL, linked to a news article about the event and commented “Hahahahaha love this, maybe people shouldn’t block roads.” Recently released screen captures from the chat rooms where Unite the Right organizers discussed the event show them worrying about their ability to leave the rally site safely, and wondering about the legality of running over counter-protesters. It’s possible Fields participated in this chat, or knew someone who did.

The Trump phenomenon is, if anything, a mobilization of this sort of homicidal chatter, with the police vote and police consciousness at its center. Though Islamophobia and racism directed at immigrants from Mexico and Central American dominates, there is a deep and arguably central current of anti-black racism at work in the Trump vote and in particular among his frothiest alt-right supporters. His “law and order” rhetoric always had the antipolice riots of Ferguson and Baltimore in the background. In an early statement, his administration wrote: “Our job is not to make life more comfortable for the rioter, the looter, or the violent disrupter” and one of his first executive orders instructed the Attorney General to devise new criminal statutes for attacks on police and use existing statutes to exact the maximum punishment possible. The federal prosecution of inauguration protesters — 187 of whom are facing decades in prison for simply attending a protest in which attacks on police occurred — is evidence that the Department of Justice is following through on these commitments.

In some states, cops drive Challengers. The one James Alex Fields drove wouldn’t have been suited for police work, however. It has a V6 engine that gets a mere 250 horsepower as opposed to the ridiculous 700 horsepower one can wring from the supercharged V8 models. This makes it even more the image of white revanchism, a simulacrum of All-American automotive strength built around an engine that could barely beat a Toyota Prius in a race. It is a car for men who secretly worry they are “beta” rather than “alpha” males. And yet, it still weighs close to two tons and, at the relatively modest speed of 40 mph, is as deadly as they come. Whether or not his car could have sirens strapped onto it and serve as a cop car, Fields was truly the vanguard of a widespread American fantasy. He merely realized the wish uttered by tens of thousands of the worst people in the country.

On the day that Heather Heyer was killed and DeAndre Harris nearly beaten to death in a parking lot and dozens of other protesters injured, notice of spontaneous solidarity demonstrations quickly diffused throughout social media. The crowd gathered in Latham Square in Oakland was surprisingly large for such a last minute call, well over the 500-person mark. After 45 minutes of speeches I could barely hear, we took the streets, walking up Broadway, through Chinatown, and along the east side of Lake Merritt. People honked their horns and waved, jumped into the crowd and walked with us for a few blocks, dancing to the music from the mobile soundsystem. In Oakland, if you tell people what the protest is about they shake their head in commiseration and utter a few words of support. At the top of the lake, the police had blocked off the entrance to the 580, as they often have since the high point of the freeway blockades a few years ago. That tactic had seemed to die out here, partly through overuse and partly through more effective policing. Arguably, there are more pointed types of blockades than those that target a random group of drivers trying to get somewhere. The Standing Rock blockades would be one example, as would the shutdown of the port of Oakland during the Occupy movement. But deindustrialization, in addition to fertilizing the ground from which nativism of Trump and his followers emerges, also leaves those who would resist it without the primary weapon of the weak for most of the 20th century: the strike. People with no jobs, or with jobs in precarious workplaces, need to find some way to make their power felt, to make a largely indifferent world come to a halt. So they occupy, they blockade, they riot.

That night, police had blocked the on-ramp but for some reason left the off-ramp unguarded. The crowd surged toward it, spilling through the backed-up cars exiting the freeway and making it impossible for the police vehicles to follow. A line of protesters stretched across all 8 lanes. Colored smoke bombs and fireworks exploded, in mourning, people said, for Heyer and all the victims in Charlottesville, but also in celebration of what had been a real victory. They chanted: “Whose streets? Our streets!” and “Black Lives Matter.” This is apparently what the crowd run down by Fields had been chanting. Four highway patrol on motorcycles yelled through their loudspeakers “Get out of the road! Now!” But until reinforcements arrived, all they could do was yell.

Jasper Bernes is the author of We Are Nothing and So Can You (Commune Editions, 2015) and The Work of Art in the Age of Deindustrialization (Stanford, 2017). He lives in Berkeley with his family.

[book-strip index="1" style="display"]