The Myth and Reality of Brexit and Migrants

Rebecca Omonira-Oyekanmi is a journalist and writer-in-residence at Lacuna. Through interviews with Thamer, a Syrian refugee, and Mahalia, a survivor of domestic violence and migrant, Omonira-Oyekanmi demystifies two common narratives in the Brexit campaigns that play on anxieties around immigration and resources.

The official campaign to leave the European Union was based on two xenophobic myths, woven into public discussion. Subtlety was unnecessary because these ideas around immigration had been decades in the making: the media led the narrative, the public understood it and politicians whipped it out whenever things got tricky.

Myth One: Take Back Control

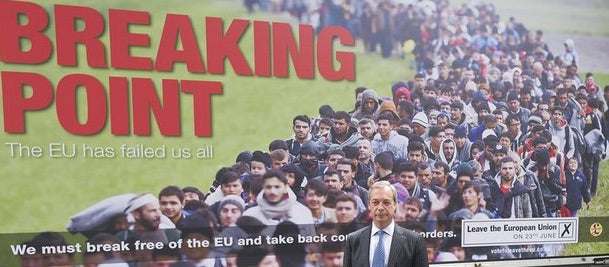

The first myth was that leaving the EU would shield Britain from the refugee crisis and stem the flow of people seeking sanctuary on these shores. This undertone was made explicit by Nigel Farage’s ‘Breaking Point’ poster, which pictured Middle Eastern refugees queuing at Europe’s borders. The subheading read: “We must break free of the EU and take back control.” There was little ambiguity. Taking back control was about keeping this particular group of people out. And this is what many voted for. This is regrettable. Because in reality Brexit will have no bearing on those seeking sanctuary from war and persecution.

When the people of Syria took to the streets in March 2011, Thamer was there, leading the cries for freedom. For much of his four decades, Thamer, a human rights lawyer, poet and academic cloaked his criticism of the government in the dry language of academia or disguised it with humour. In 2009, he published a collection of short stories, gently mocking the authoritarian regime of Bashar al-Assad. “When you want to write about the government in Syria … you change the names or change the places. Or you replace them with animals.”

But the time for secrecy had passed. Thamer watched governments in Egypt and Tunisia topple, and felt optimistic. Here was a chance for peaceful revolution, for the Syrian people to come together and demand their rights. Thamer committed himself to the protests. Looking back at this time, in moments of sadness, his wife Rashida regrets the choice her husband made because it would change their lives forever. He always had to fight, to help people in Syria for freedom. Why, why, why?

It didn’t take long for Assad’s security forces to identify Thamer and over the course of three months he was arrested, tortured, released, arrested, tortured, released. He continued to stand with the protestors and one several occasions Assad’s police attempted to assassinate him. Thamer survived and fled to Jordan, arranging for his wife and their four children to follow shortly afterwards. In Jordan, he felt uneasy, certain that Assad’s forces were at work there. The Jordanian government did their best to protect him, offering him a bodyguard, but fellow comrades were killed. Thamer made the decision to move again.

There were other factors in the decision to move. Jordan was – is – a tough place for Syrians, there was little work and while Thamer’s family were lucky enough to have a house to live in, it was overcrowded, open to whoever managed to escape Assad’s deadly aim. Rashida would cook and clean, day and night for the passing revolutionaries, all the while her own nerves frayed as her parents remained in Aleppo, bombs falling about them. By now, Thamer’s thick dark hair had turned a shocking white, the torture had ravaged him mentally and physically; his back was a source of constant pain and his mind slipped from his grasp where once it was agile. He became distant with his family, but he was thinking about the future, his children’s future. The war showed little sign of abating and the international community dithered. Syria was the past, it belonged to him and Rashida, but perhaps the children could have a future somewhere else. He chose Britain. “The UK is the first state in the world for human rights. English is the first language in the world. This is the language for science, the new, everything. A good future for my children.”

Thamer flew from Jordan to Paris, then to London, where he claimed asylum. A day later he was sent to Glasgow, where he now lives with his family. It took more than a year for Thamer to secure visas for his wife and children to join him in the UK under the country’s family reunification rules. The entire process was fraught, despite the strength of the family’s case. An exhausted Rashida had to convince the British embassy in Jordan that Thamer was her husband and that her children were her children. Meanwhile, there were regular reports from home of the deaths of friends and family. Thamer’s mother died of a brain haemorrhage because it was too dangerous for her to leave the house to get to a hospital, just a few hundred metres away.

Thamer and Rashida still live the horrors of the Syrian war, but their children are safe, and already their Syrian accents are giving way to a thick Glaswegian lilt. The hope Thamer had in 2011 when he took to the streets is now the hope for them in a new country, with a future free of Assad and his bullets.

Bullets that are still being fired. Which brings us to the point. Whether or not Britain leaves the EU, there is a war in Syria and refugees in its neighbouring countries live in squalid conditions. Thamer wasn’t exercising free movement within the EU, or coming as an economic migrant, he was fleeing war. Whether or not Britain leaves the EU, the UK is a signatory to the refugee convention and is obliged to do its bit for people fleeing persecution (the dereliction of that duty thus far is another story). Our obligations to him and his family won’t – and should not – change because of Brexit.

Myth Two: The Migrant Benefit-Scrounger

The second xenophobic myth peddled by both Leave and Remain campaigns was that migrants are a burden on the welfare state and live an easy life here at the expense of British citizens. This was a myth both campaigns were comfortable with because it is one that has been perpetuated consistently for about two decades. We know it well. During the 90s it was tales of bogus asylum seekers. Today the language has changed slightly, with newspapers happy to use the word ‘migrant’ as a catch all term for ‘bad migrant’. Stories abound of Eastern Europeans, Muslims, black Africans, either queuing at Calais or simply turning up and expecting handouts. Even the left has capitulated to this myth; what to do about these problematic people and the pressures they place on the country has become one of the political questions of our time. Thus the demonization of the poorest migrants became de rigueur, resulting in a decade or more of government policies whose effect has been to criminalise this group. The evidence is in the 3,000-strong detention estate and regular mass deportation flights to Britain’s former colonies carrying hundreds of people that have spent their formative years in this country. The evidence is the destitution of refused asylum seekers and EEA migrants with restricted access to public services and social housing. The evidence is in recent immigration legislation which gives power to doctors, bankers, landlords and others to act as border guards, policing the legality of anyone who appears foreign. The evidence is in the story of Mahalia*, a young Pakistani woman who arrived in the UK in 2012 after an arranged marriage to a British citizen.

Mahalia was treated as a slave, made to cook and clean for her husband and his extended family, and regularly slapped and taunted. Her husband was the most violent, either kicking her in the stomach or punching her face, depending on his mood. Her mother-in-law and father-in-law, would slap her occasionally and always shouted and cursed her, even once taking away her baby for a few days because she struggled to stop the child’s crying. It was easy for her husband to control her movements and limit escape routes; he prevented her from attending English classes and made no attempt to regularise her migration status. Once her spousal visa expired, if she tried to report him to the police she risked deportation.

One winter, Mahalia ran away and, unsure of what to do, she went and sat in her local park. A family friend discovered her and took her home, aghast at the young woman’s story. But her mother-in-law called the police, who escorted Mahalia back to the family home, where her husband tried to suffocate her. He then pummelled her stomach his feet, pulled her hair and punched her head against the wall. This time she called the police.

If Mahalia was a British citizen she and her daughter could claim housing benefit, which would cover the cost of a bed at a domestic violence refuge. But she is a migrant with uncertain status, which means that she can’t easily access this support. When Mahalia turned up on their doorstep, several refuges turned her away because they assumed she had no access to benefits and couldn’t cover the cost of her stay. Still traumatised and unable to speak confidently in English, Mahalia and her little daughter stayed in homelessness hostels, mixed sex hostels for refugees and hotels, while she attempted to gather evidence needed to sort out her migration status and get access to support.

Persevering, Mahalia worked on her English and began to gather the evidence she needed to prove that she had been abused and to regularise her status. She does all this from a Travelodge, where she and her daughter live in a small room with no cooking facilities. Sometimes she’s afraid to leave the room, but she must because her daughter is full of energy and needs space. Every week she visits Safety4Sisters, a migrant women’s rights group that campaigns on issues affecting undocumented women experiencing gender-based violence. It is here that Mahalia learned she might be eligible for support under the Home Office’s domestic violence spousal visa exception, yet all the services she came into contact with assumed that, as a migrant, she was entitled to nothing.

Mahalia isn’t an isolated case, there are hundreds like her and many have no access to public funds. Other abused women continue to live with their violent partners for this reason. This is hardly the ‘easy’ life of a lazy scrounger getting handouts from the welfare state. If you are a poor migrant in Britain today, just as is increasingly the case for British citizens, there are few safety nets to catch you if anything goes wrong. It is hard to see how the Leave campaigners might seek to make Mahalia’s life any more difficult than it already is.

These are profoundly uncertain times; there are calls for a second referendum, the possibility of a general election and maybe a referendum on Scottish Independence. Whatever happens, the public debate will continue, and we need to address the myths and face the reality. British people must be given the opportunity to make up their own minds about the reality of migration in this country based on truth and not lies.

*Mahalia’s name was changed to protect her identity.

I met Thamer and his family through Freedom from Torture, a charity that treats and supports torture survivors across the UK.