'Never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again'—The Madness of Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Alice Spawls revisits the life and work of socialist feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman and explores the psychological effects of gendered oppression for World Mental Health Day 2015.

Gilman was a writer, editor, economist, and theorist who advocated for women's suffrage, economic independence, birth control and the transformation of domestic life, as well as democratizing everyday culture and relationships. Her skill, Sheila Rowbotham observes, "lay in elaborating the ordinary annoyances of women’s lives into topics of intellectual debate, while making utopia seem like a new common sense." She is perhaps best known for her striking short story The Yellow Wallpaper (1890) chronicling the mental breakdown and physical crisis provoked by the constraints of being a wife and mother.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman at her desk writing, ca. 1916-1922

Charlotte Perkins Gilman always travelled with two books in her trunk: Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass and Olive Schreiner’s Dreams. She wouldn’t have been surprised that it is Whitman we know still, though she may have been disappointed that Schreiner’s dedication – ‘To a small girl-child, who may live to grasp somewhat of that which for us is yet sight, not touch’ – has not been more fully realised. Gilman saw herself as a ‘transition woman’, borrowing the term from Schreiner. Her generation, middle-aged at the turn of the 20thcentury, would, she thought, suffer and sacrifice for the benefit of their daughters: they – or at least she – would dedicate themselves to activism; carving out a place for women in the world. ‘Work first, Love next,’ she wrote, ‘the world’s Life first, my own life next.’

She made that sacrifice, starkly, in leaving her marriage and her young daughter. In 1884 she had married Charles Walter Stetson. Her first response had been to refuse him and pregnancy confirmed her instinct. It is often said that she suffered post-partum depression; no doubt she did. It is often said that the story she wrote about the experience, The Yellow Wallpaper (1892), is a gothic tale; perhaps it is. But both accounts fall short. To read The Yellow Wallpaper as a sinister tale, as one woman’s hysteria, is to miss the whole point: the political charge that led to calls for it to be ‘censored’, where writers like Poe were not. The narrator is a young woman who, like Gilman, depressed after the birth of her first child is advised by a (male) doctor to take complete rest: to separate herself from her child, to undertake no work. Gilman was told ‘never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again’. In the story, the narrator’s husband is also her physician – maritus, medicus. He rents a house for the summer and installs her in the upstairs nursery (an infantilisation?) where the sickly yellow wallpaper, redolent of ‘old foul, bad yellow things’, of stagnation, waste and decay, takes hold of her. She begins to see the figure of a woman crouching and creeping around in the wallpaper’s foliage, like a Kara Walker cut-out, and grows obsessed with freeing her. In the final scene she tears the wallpaper from the walls and gnaws the bed; herself and the creeping woman inseparable – freeing the one to free the other. Is she mad? I don’t think so. Troubled, constrained, frustrated: certainly. The story is a parable (better than any of Schreiner’s) and Gilman, who was suspicious of fiction on the whole, wrote it for one end: to reflect the horror of her confinement; to ‘reach Dr S. Weir Mitchell [her doctor] and convince him of the error of his ways.’ More recent descriptions of the story as a memoir of Gilman’s descent from depression to psychosis is enough to make anyone depressed – at the failure to expose a social problem rather than render it a personal weakness.

John, the husband in the The Yellow Wallpaper, is not bad, not insensitive or unusually cruel; nor was Charles, quite the opposite. But neither could see beyond their received ideas about women and wives. Charles was left despairing of having married Charlotte, distraught at having caused her so much pain. He ‘set her free’ to ‘preach’; seeing in her not a natural wish to retain an independent self but a messianic desire, a calling. She was active in social reform movements, lectured extensively and in 1896 attended the International Socialist and Labour Congress in London. Her two years of editing the Women’s Press Association magazine, The Impress, ended in part because of her unconventional lifestyle; from 1909 to 1916 she singlehandedly wrote and edited The Forerunner, a vehicle for her ideas and a progressive counterbalance to the dominant Ladies’ Home Journal.

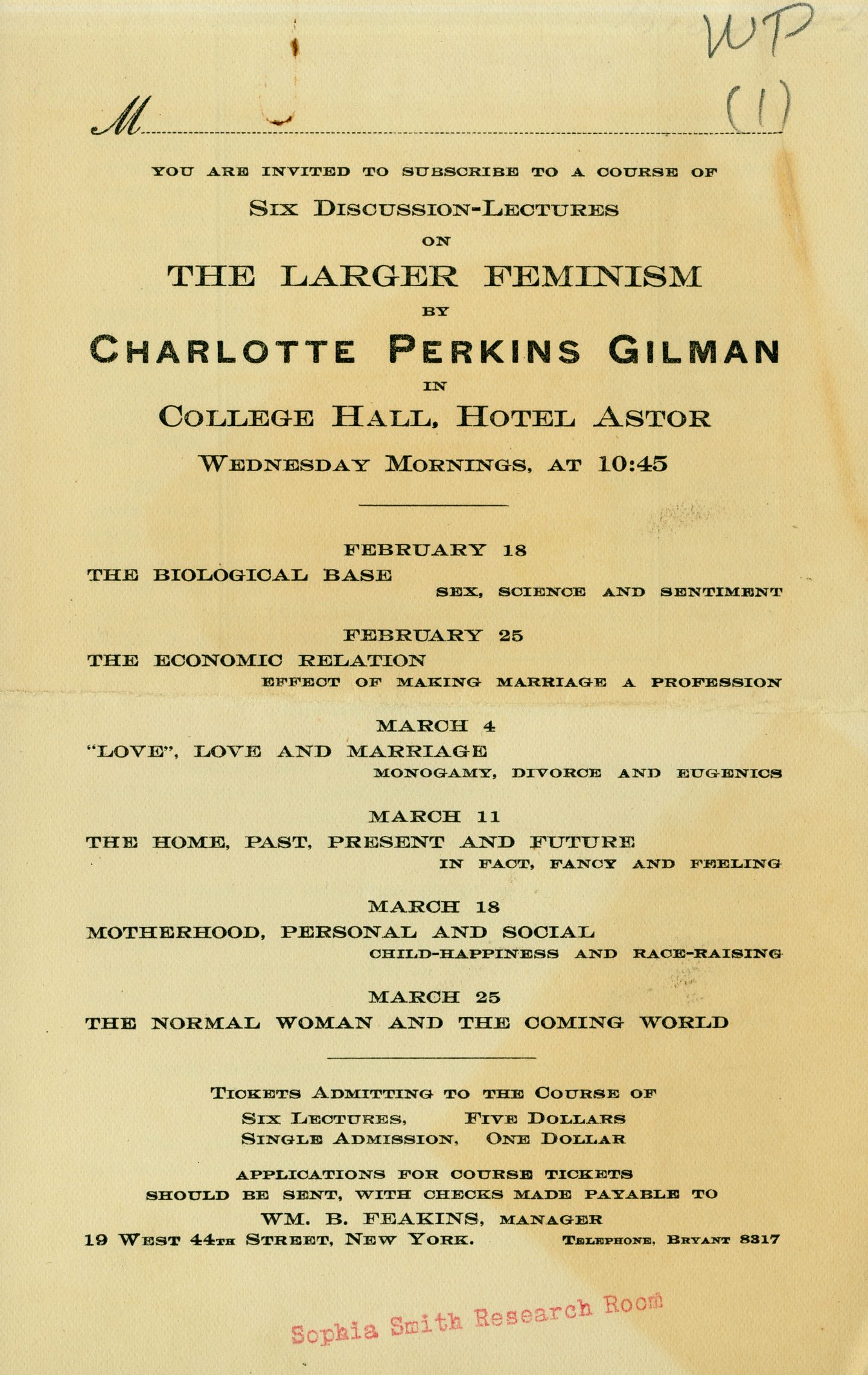

Brochure advertising lectures by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

But Gilman’s drive, while uncommon, was not bizarre. Schreiner travelled in her trunk because of its allegorical feminism; Whitman because he sang of himself and yet contained multitudes. In Gilman’s work – three poetry collections, 186 short stories, seven longer works of fiction, 11 non-fiction books, numerous shorter works, plays, dialogues, articles, letters, journals and an autobiography – she stresses again and again human-ness, man and woman’s common humanity. In The Man-Made World; or, Our Androcentric Culture she turns what seems to be a biologically reductionist argument on its head: sheep and goats and cows may all naturally perform gendered roles, but human intelligence is such that we are united at a level far beyond these most basic divisions. But Gilman doesn’t reject biology altogether. Across her works she draws the distinction between ‘natural’ and ‘human’ institutions. Those which she considers natural, whether God-given or Darwinian (and she sought to reconcile them), are those which benefit our fundamental natures and society as a whole: physical exercise, monogamy (but not celibacy), the family – though not the nuclear family dominated by the father/husband: ‘Friendship does not need ‘a head’. Love does not need ‘a head’. Why should a family?’ Human institutions, like the home, can be changed and improved. She argued that men had upset and overruled the natural sexual selection prerogative of women; an idea which suggests androcentric culture structuralises rape (or at least, coercive sex). She thought that universal suffrage was a human right but not nearly enough in itself—the emancipation she envisioned would require an overhaul of social structures and a revolution in personal relationships:

The political equality demanded by the suffragists [is] not enough to give real freedom. Women whose industrial position is that of a house-servant, or who do not work at all, who are fed, clothed, and given pocket-money by men, do not reach freedom and equality, by use of the ballot.

History, Gilman pointed out, has been written by men. Our Androcentric Culture is valuable not least for its bleak range of late 19th and early 20th-century quotes about women, by men, from the doctor who says that women ‘are not even half the race, but a subspecies for reproduction only’ to the journalist who claims that the modern woman’s ‘constitutional restlessness has caused her to abdicate those functions which alone excuse or explain her existence’. She addresses the question of genius: ‘the greatest milliners, the greatest dressmakers and tailors, the greatest hairdressers, and the masters and designers in all our decorative toilettes and accessories, are men’ because the professionalised world has hitherto been dominated solely by men. Women are consumers of worldly things and creators only of primitive, homely things. She doesn’t quite say that textiles and crafts should be seen as high art, but that where (and when) a man excels in a ‘female’ discipline it becomes elevated only in relation to him. It is not that the male brain is different from the female, more suited to genius – ‘you might as well speak of a female liver’ – but rarefied forms of art are products of patriarchy and therefore may never admit women. The implication, though she didn’t make it, is of cultural superiority and appropriation across class and race, as well as between sexes.

Romantic novels she saw as simply repackaging conquest narratives (‘why do the stories stop at marriage?’); leisure and exercise as the unfair domains of men – just as we still see at the park or pub. Child-rearing is scarcely less gendered than it was when she wrote of the horror of providing little girls with babies ‘before they cease to be babies themselves’, while not expecting ‘the little boy to manifest a father’s love and care for an imitation child’. Socialism and women’s suffrage were dual extensions of her humanism: just as slavery had been abolished, so would any claims to rights over women and communal infrastructure (though not private homes). Gilman read widely – and was widely read. It’s a shame that the Wikipedia page on one of her most important books, Women and Economics, is so concerned with the male writers who are said to have influenced her. Apparently Gilman ‘borrowed’ from Marx, ‘used’ Darwin, ‘took’ from Veblen, ‘borrowed’ from Lester Ward and was ‘influenced by’ Edward Bellamy. The intention seems to be to reduce Gilman’s thought to a mere corollary.

Many of her best works – Women and Economics, Our Androcentric Culture, The Home: Its Work and Influence – are out of print (though available freely online). Her many articles, with such wonderful titles as ‘A Protest Against Petticoats’; ‘How Much Must We Read’; ‘What ‘Love’ Really Is’ and ‘Gum Chewing in Public’, ought to be collected, along with contemporary criticism (for amusement at least: one headline in The New York Times ran: ‘Adam the Real Rib, Mrs Gilman Insists’.) Her arguments for the recognition of domestic labour pre-empt many later feminist causes, including Wages for Housework:

If the wife is not, then, truly a business partner, in what way does she earn from her husband the food, clothing, and shelter she receives at his hands? By house service, it will be instantly replied. This is the general misty idea upon the subject,– that women earn all they get, and more, by house service. Here we come to a very practical and definite economic ground. Although not producers of wealth, women serve in the final processes of preparation and distribution. Their labor in the household has a genuine economic value.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman on Seattle suffrage trip, ca. 1900

Gilman saw women’s unwritten historical contribution to human society – as mothers, cleaners, cooks, sexual partners, carers, educators – as fundamental to its progress and success, but inherently limiting. She makes the case in numerous books and articles for how much happier and better life would be if only men accepted women as their equals rather than their subjects. She doesn’t consider that patriarchy might be constructed around a fear of women, an attempt to control their bodies and minds; rather it seems to her illogical that anyone who believes in social progress would wish to limit half the population. But her recognition of the necessity of men in furthering women’s freedom was quite right: ‘It is a sociological impossibility that a majority of an unorganised class should unite in concerted demand for a right, a duty, which they have never known.’

Long before Judith Butler, Gilman’s utopian novel Herland, about a society of self-propagating women, suggested that gender roles were social constructs. The women of Herland don’t exist in relation to men but simply as people. Motherhood is central to their lives, but the tasks of caring and educating are shared among the community, much like the collectives of the 1970s and 80s. The three men who arrive in Herland all react differently: Jeff is admiring and accepting – he stays; Van is frustrated but eventually forms an equitable relationship with a woman who returns with him; Terry cannot adjust to these ‘new women’ and his attempted rape of Alima sees him banished. Van tries to explain to the women of Herland why he doesn’t consider it a crime: ‘after all, Alima was his wife’.

Herland wasn’t published as a book until 1979, and has long been neglected (a Vintage edition came out earlier this year). It has many flaws – the writing (‘her blue eyes swimming in happy tears, her heart lifted with that tide of race-motherhood’), the utopianism, the appeal to men in their goodness (as Van says, ‘You see, I loved her so much that even the restrictions she so firmly established left me much happiness.’), the uniformity – and conformity – of the women, the obsession with motherhood. Some of Gilman’s assumptions – about race especially – go unquestioned. But as a document it’s remarkable; its central question, what would a society without men be like for women?, no less critical an exercise (or exciting a daydream). Gilman appealed to both the suffragette and the socialist in Herland, but it’s the suffragette who gains most: a world free from male desire and male violence, male dominance, male establishments, male language; where women are unselfconsciously first, normal, prevalent, universal.

Gilman argued that the sexes were exaggerated in their difference by patriarchal culture in order to limit and objectify women: the greater the difference, the greater the sexual attraction. ‘What man calls beauty in woman’, she wrote,’ is not human beauty at all, but gross overdevelopment of certain points which appeal to him’. Androgyny was her preferred solution. The women of Herland wear tunics and short hair; their physiques are slim and strong: they easily outrun the men. In relation to the sex-seclusion of veiling and foot-binding she discusses elsewhere – done by women to women, though not for their benefit – the utilitarianism of Herland seems immensely liberating, but like all utopias it allows little room for individual difference, for creativity, for subversion.

Gilman was so prescient that now, over a hundred years later, it is remarkable to see how often she was right and yet how little has changed. Many of her ideas have been accepted but not acted on; her theoretical dilemmas have emerged but remain unsolved. She argued for the importance of work to women—as economic necessity and engagement with the world, to live autonomously, free from financial dependency on men . The son, she writes, ‘considers the home as a place of women . . . and longs to grow up and leave it – for the real world. He is quite right. The error is that this great social instinct . . . is considered masculine.’ She doesn’t imagine a society in which private and public labour is afforded equal value – to her mind they can’t be; her early recognition that were she to marry ‘my thoughts, my acts, my whole life would be centred in husband and children’ is seen as a terrible social conditioning that can only be avoided by escaping those roles (though her later, childless marriage to Houghton Gilman proved more satisfactory). She imagines a world where women and men both work, and childcare and food provision is centralised in buildings and communities – shared kitchens, private dining rooms – but she doesn’t address who will do the cooking and cleaning. Gilman’s ‘woman’ is a woman like herself – middle-class (not having to work but not free from all housework), educated, Anglican, white. Two of her most significant relationships were with women, but neither in Herland nor in her autobiography does she admit women their full range of sexual feeling. She has been criticised for her contradictions – promoting motherhood yet abandoning it herself, rejecting and accepting marriage, living too individualistically for her socialist credentials, being too dependent on Houghton for her feminist ones (she wrote of hiding in his overcoat pocket like a Newfoundland puppy) – but it’s hard not to see in her life, if not in her work, all the difficulties faced by women who don’t live in Herland, who don’t want to choose between careers and children, feminism and love, being alone or subjected; who want to believe that their relationships and their choices might work out differently.

Alice Spawls is an artist and writer. She works at the London Review of Books