Henri Lefebvre: Dogmatism in Reverse

Anti-Stalinist Communist, intellectual figure of May 68, Henri Lefebvre is re-read today as an ecosocialist thinker. His political quest for a balance between radicalism and mass movement is as relevant today as his thought, which is resistant to dogmatism.

This article was originally published by Mediapart on 12 Aug 2023.

In 1958, during the insurrectionary events that preceded General de Gaulle’s return to power, 57-year-old Henri Lefebvre faced two ‘comrades’ from the French Communist Party in an austere room. His request for minutes to be taken had just been curtly refused. The Commission central de contrôle politique was only there to question him about his ‘behaviour’.

The interview began: ‘Did you ask the Party’s permission to write an article about the Nouvelle Vague in L’Express?’ – ‘No.’ – ‘Did you ask the Party’s permission to write a response to André Philip in France-Observateur?’ – ‘No.’ After this comedy of an interrogation, the philosopher was expelled from the PCF, in which he had been an activist for thirty years. He was part of the first generation of Marxist philosophers, along with his friends Norbert Guterman (1900-84) and Georges Politzer (1903-42).

In his critical autobiography, La Somme et le Reste (1959) – a remarkable book, published in two volumes and unfortunately difficult to consult today, like much of his prolific work (some 60 books) – he comments: ‘The leaders judged the time had come and the moment was favourable to get rid of the anti-Stalinist opposition.’

Since the publication of Khrushchev’s report to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956, Lefebvre’s relations with the nomenklatura had been strained. In 1957, the General Secretary of the PCF, Maurice Thorez, filled his most recent book (Pour connaître la pensée de Lénine) with handwritten comments, accusing it of ‘revisionism’ and ‘convergences with the New Left’.

Lefebvre’s attachment to the idea that the philosopher must ‘unmask and root out alienation in all its forms, from the holy image (religion) to profane representations, including political alienation and philosophical alienation itself’, irritated the Stalinists, who clung to their monolithic ‘diamat’ (dialectical materialism). They rejected Marx’s early work (the famous Manuscripts of 1844), which Lefebvre had been the first to publish in French in 1933, in the journal Avant-Poste, and in which Marx had defined the concept of alienation.

In 1958, the break was complete. On 1 March, Thorez put ‘the fight against revisionism (H. Lefebvre)’ on the agenda of a meeting with Roger Garaudy (1913-2012), a rising figure in the PCF. The party functionaries did their utmost to record this disgrace. In La Nouvelle Critique, then in a whole book, Lucien Sève (1926-2020), another intellectual figure in the Party, completed the philosophical execution (which he regretted at the end of his life).

Lefebvre summed up his own faults with irony: ‘I had fought against dogmatism, against Stalinism, for democracy in the Party, for a programme for the Left.’

This excommunication, at a time when Marxist thought was hegemonic and the PCF won a quarter of the national vote, had a lot to do with the minority reception of Lefebvre’s work in France. ‘His expulsion led to Lefebvre being sidelined for decades. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Communists rediscovered his ideas, which had been rejected as heretical,’ explains the historian of communism Roger Martelli, who knew him at the end of his life. This former member of the PCF’s ‘Refondateurs’ movement remembers him as a ‘fascinating figure, who commanded respect for his rigour and his intellectual ability to understand the movement of societies’. A part of living history, therefore.

[book-strip index="1"]

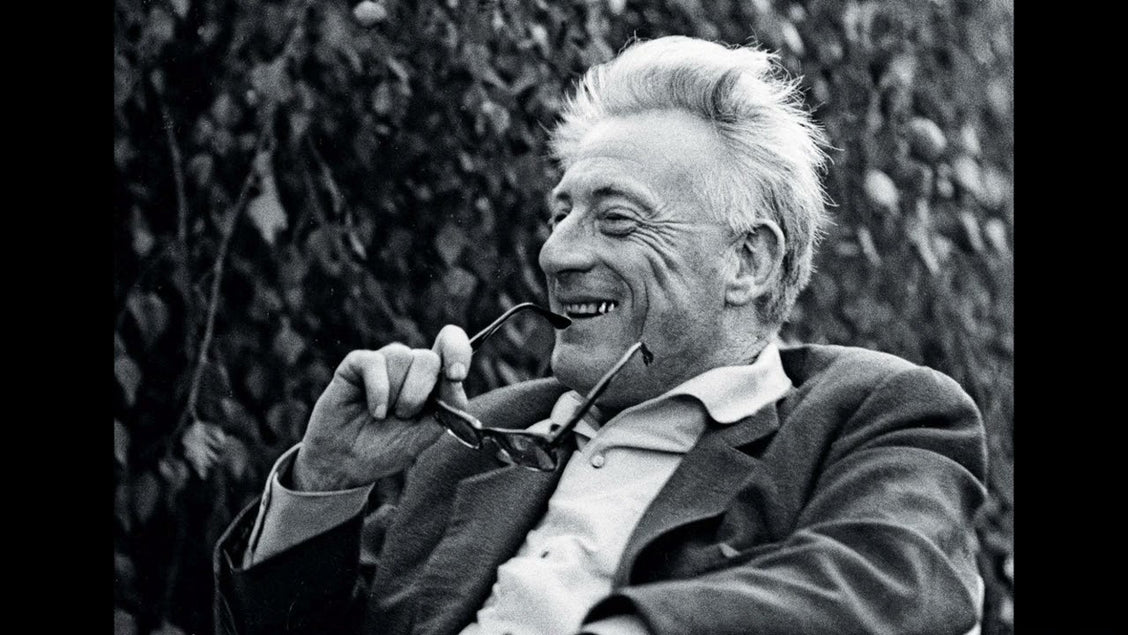

Born in 1901 and dying in 1991, Lefebvre lived through what Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm called ‘the age of extremes’. ‘His work is a strange encounter between philosophy, the 20th century and Marx’s early texts,’ says his daughter, Armelle Lefebvre, herself a philosopher, who is in charge of the 150 boxes of her father's archives entrusted to the Institut mémoires de l’édition contemporaine (IMEC). Henri Lefebvre joined the PCF in 1928, was expelled in 1958, was at the heart of May 68 (he was teaching at Nanterre at the time and claims to have played a role in the formation of the 22 March group), flirted with the Situationists (a left-wing group around Guy Debord), and died at the same time as the collapse of the USSR.

For a while, unexpectedly, he became closer to the PCF, of which his last wife, Catherine Régulier, was a member, and even asked to be reinstated. ‘He asked that this reinstatement take the form of a rehabilitation, in the context of a reception by the leaders of the PCF. He received no response,’ reports historian Yves Vargas. At the very time of his expulsion, he published a response with an eloquent title in Les Temps modernes: ‘L’exclu s’inclut’ (‘The excluded includes himself’). ‘He always loved taking a stand, he wouldn’t let himself just be cut off,’ Armelle Lefebvre explains.

For Roger Martelli, this unexpected return to the ‘great party of the working class’ was a generational affair: Henri Lefebvre, like the historian Jean Bruhat (1905-83), had seen the PCF grow from the marginal position of its early years (after the Tours Congress in 1920) to the mass party of the Popular Front and the Liberation. ‘His ability to combine a radical critique of Communism with a sense of mass struggle kept him away from the Trotskyist and Maoist far left. This experience of popular radicalism remains a central issue in political life today, and that’s where the Left is lacking’, observes Roger Martelli. This is one of the reasons why La Somme et le reste strangely echoes the contemporary vicissitudes of the Left. The fight against dogmatism and the inward-looking attitude of left-wing parties (‘I don’t want to endorse dogmatism just because a useful ideological instrument [i.e. the PCF] takes this form’), the impasse of the PCF’s national turn – the subject of his book Le Nationalisme contre les nations, published in 1936 (‘After having strengthened the nationalist current, after having weakened and contributed to splitting “the left”, the Communists have not succeeded in reintegrating themselves into it’) – the need to ‘break down the barriers’ between ‘the Left’ and the Communist movement, the attachment to democracy and spontaneity, are all themes of his that still resonate.

Celebrated in May 68, then suddenly forgotten

For all that, Henri Lefebvre’s philosophical voice does not reach us easily. The historian Jean-Numa Ducange, who is working on Lefebvre’s archives, notes a ‘very great disproportion’ in the dissemination of his thought. While his seminal works on urbanism (Le Droit à la ville [1968], Du rural à l’urbain [1970], and La Production de l’espace [1974])[1] are ‘an absolute reference in English-language urban studies’, Lefebvre is relatively marginal in France. Sebastian Budgen, senior editor at Verso, which has published seven of Lefebvre’s books, confirms that there is a ‘huge gap in his reception between France and the English-speaking world… From the adoption of his book, Le Droit à la ville, by the current of radical geographers, first and foremost David Harvey in the 1980s, he has become an essential reference for major thinkers of radical criticism, whereas he is little discussed among contemporary philosophers and sociologists in France.’

In France, Lefebvre’s publishing history has been less straightforward. Incongruously, his most important books are published by Economica, a publishing house that does not specialise in the humanities and social sciences. His most widely distributed book is a ‘Que sais-je?’ volume, Le Marxisme, that has been constantly republished since 1948. Gallimard even reverted the rights to La Proclamation de la Commune, published in 1965 in the famous collection ‘Trente journées qui ont fait la France’; La Fabrique reissued it in 2018.

‘This work was a monumental success in the 1970s,’ explains Jean-Numa Ducange. Far from ideological stereotypes, the author – who discussed it over many a drunken night with the Situationists and was even accused by them of plagiarism – interprets the Commune as a reappropriation by the working classes of the districts from which they had been excluded by Haussmann. ‘According to classic Communist doctrine, the Paris Commune heralded twentieth-century Communism, and all it lacked was a Bolshevik party. Lefebvre departs from this reading to emphasise its libertarian aspects, its discovery of autonomy, which was later confirmed by the historian Jacques Rougerie,’ analyses Roger Martelli.

With his combination of disciplines – philosophy, sociology, urbanism, history – Lefebvre applied his Critique of Everyday Life (one of his most influential books, first published in 1947), in which he argued that everyday life is the actual site of class domination), to the Paris insurrection. It was ‘the metamorphosis of (everyday) life into a never-ending party, a joy with no other limit or measure than the inevitability of death, itself indefinitely postponed’. The explosion of May 68 and the leftist effervescence that followed placed the book and its author at the heart of the times. Seeing revolution as a party appealed to these enragés.

With a front-row seat to the revolt (he taught in lecture hall B2 at Nanterre, where the events began), Lefebvre pioneered an original interpretation – the theory of spatial contradiction – which has become an established part of the historiography of May 68: the location of the nearest métro station meant that Nanterre students had to cross the Algerian shantytowns every day to get to their brand new campus. ‘The students became very aware of the realities of the world. For Henri Lefebvre, this was one of the root causes of the student revolt,’ explains Armelle Lefebvre, who remembers that her father often told this story.

Here again, however, Lefebvre’s fame came up against his iconoclastic character, which ran counter to the dominant currents of Marxist thought. He was violently opposed to structuralism and existentialism, and railed against Louis Althusser (1918-90), who reigned supreme at the École Normale Supérieure. Lefebvre was neither a normalien nor an agrégé. ‘Lefebvre and his friends didn’t believe in the academy, it was the wrong place to be. In fact, he was over 60 when he started teaching at Nanterre,’ his daughter recalls. But history remembers academics more than regular folk, argues the sociologist Rémi Hess, his biographer, who reports in his preface to Le Droit à la ville that Lefebvre ‘studied sociology by driving a taxi in 1920s Paris’.

[book-strip index="2"]

Contacted by Mediapart, the philosopher Étienne Balibar, who was a student of Althusser and himself a graduate of the École Normale Supérieure, confirms this marginalisation based on theoretical differences. He reports that he only met Lefebvre late in his life, in 1978, at a dinner at his home hosted by the philosopher Nicos Poulantzas (1936-79). Poulantzas, tragically aware of the divisions on the political and intellectual left, wanted to reconcile the fraternal enemies Lefebvre and Althusser. The author of Reading Capital never turned up.

Balibar, on the other hand, was won over by the philosopher with a Victor Hugo profile, ‘very sharp intellectually, and tremendously attractive’. Lefebvre then suggested that he and Balibar write a book on Marxism, to ‘make a splash’ among Marxologists, who would not have expected it. Balibar declined, not out of reserve, but because the contract already signed with the publishing house gave them just two weeks – a prospect which did not frighten Lefebvre, an incomparably breakneck writer. ‘I was devastated,’ says Balibar. ‘I’d deprived myself of the pleasure of writing a book with him.’

The rediscovery of an ‘ecological thinker’

For Kristin Ross, professor of comparative literature at New York University and a champion of Lefebvre studies, there is another reason why the philosopher has received so little attention in France compared with the English-speaking world. ‘The de-Marxification of France, which began in the late 1970s with François Furet and the Nouveaux Philosophes, was far more thorough – almost a purge – than in the United States or Britain, let alone Latin America,’ she explains. ‘The fact that Marxism in American universities did not experience anything so severe, despite the McCarthy era, and that it managed to limp along its minority path, only serves to underline the remarkable strength of the hegemony of Marxist thought in philosophical debate in France after the Second World War. Lefebvre was at the heart of this intellectual and political turmoil, and he did not “turn his coat”, as the saying goes.’

In her latest book, La forme-Commune, published by La Fabrique, in which she revisits the peasant struggles of the 1960s and 1970s in the light of contemporary struggles against land grabbing (the Notre-Dame-des-Landes ZAD, Earth Uprisings), Kristin Ross draws on Henri Lefebvre as an ‘ecological thinker’, as she explained in an interview with Mediapart. Before taking an interest in urbanism, Lefebvre was a researcher in rural sociology at the CNRS, and in 1954 he wrote two theses on the Pyrenean valleys, where his mother’s family came from and with which he retained a connection.

It is this part of his work that has been the subject of exponential rediscovery in recent years. In the introduction to an unpublished text dating from 1959, projected to appear this September in issue 74 of the review Actuel Marx, Armelle Lefebvre and Claire Revol (author of a thesis on Lefebvre) highlight this topicality: ‘As the twenty-first century engages in the struggle for essential common goods (water, air, soil and subsoil, farmland and local food, forests), in a context of ecological crisis and systemic pollution, Lefebvre’s thought offers peasant struggles points of support that have already been identified, and that remain to be explored.’

[book-strip index="3"]

Describing Lefebvre as an ‘ecological thinker’, however anachronistic it may seem, is not absurd in the eyes of his daughter, quite the contrary. She reports that he was ‘very good friends’ with Bernard Charbonneau (1910-96), a precursor of radical ecology and author of the book Le Jardin de Babylone, published in 1969 and reissued by the post-Situationist publisher L’Encyclopédie des Nuisances in 2002. ‘They saw each other in the Pyrenees, where they lived 15 km apart. Charbonneau was a secondary school teacher and lived in a house with no electricity or any modern comforts,’ recalls Armelle Lefebvre, who sees in her father’s legacy the seeds of an ‘ecosocialism’.

Kristin Ross maintains that Lefebvre’s conceptualisation of the Marxist notion of ‘appropriation’ helps her to understand the strength of contemporary territorial struggles, ‘in particular this idea of reclaiming lived space and lived time’. ‘Lefebvre believed that individuals and groups could not constitute themselves as political subjects without generating a space – both physical and social – that they themselves appropriate, manage and “produce”,’ she explains. ‘This is a profoundly ecological idea, and one that is certainly at the heart of territorial movements and struggles for land restitution such as Notre-Dame-des-Landes, StopCopCity in Atlanta, Standing Rock and, of course, Earth Uprisings. Appropriation implies “use” rather than ownership.’

She adds that ‘Lefebvre wrote in a very visionary way in the 1970s about how struggles against land grabbing invariably created alliances between different kinds of people, who sometimes came together despite great ideological and identity differences – that was a process that the people of the ZAD experienced, lived and described as “composition”.’ Lefebvre’s work, long obscured in France, still deserves our full attention.

Translated by David Fernbach

[1] La Droit à la ville is translated as ‘The Right to the City’ in Henri Lefebvre, Writings on Cities (Blackwell, 1996), and La Production de l’espace as The Production of Space (Wiley, 1992). Du rural à l’urbain is translated partially in Stuart Elden and Adam David Morton (eds), Henri Lefebvre, From the Rural: Economy, Sociology, Geography (University of Minnesota Press, 2022) and as ‘Preface to the Study of the Habitat of the “Pavilion”’ in Stuart Elden, Elizabeth Lebas and Eleonore Kofman (eds), Henri Lefebvre, Key Writings (Bloomsbury, 2017).