Promise and Disappointment: Baltimore One Year After the Uprising

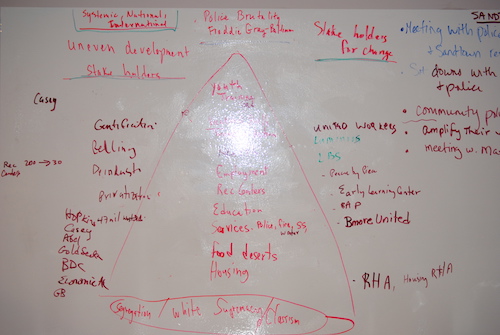

(From a meeting of Baltimore activists during the week of the curfew. Photo by Marisela Gomez)

“Last year’s uprising has created this space for my family to have this conversation. Albeit painful, its also provided us with the choice to grow from these experiences that go way back beyond the uprising.” —Daughter of a storeowner in West Baltimore, April 2016

It’s been one year since the uprising in Baltimore that followed the arrest, murder, and funeral of Freddie Gray. Mr. Gray died in police custody after a rough arrest and “rough ride”. It’s not the first time a rough ride — in which police leave a handcuffed or footcuffed person deliberately unsecured in the van, resulting in uncontrolled movement and potential injury — has accounted for the injury and death of a black man in Baltimore police custody. Following his arrest on April 12, 2015 and his death on April 19, peaceful protests occurred. After his funeral on April 27, residents of Sandtown-Winchester — Mr. Gray’s community — and others in West Baltimore affected by police brutality rose up in protest. Some protestors became violent, throwing bricks at windows, looting, and setting fire to property. The National Guard was called in, the city was placed under curfew, and tanks rolled around as if it was a war zone.

The tanks in Middle East Baltimore added to existing perceptions about the abandoned and boarded houses and businesses, the trash on the street and in the lots, the desolate look and feel at nighttime: “it’s like Beirut here," a resident told me. After real estate segregation (both legal and illegal), redlining, deindustrialization, urban renewal, mass incarceration, and gentrification, Middle East Baltimore and other black sections of the city have been subject to disinvestment and left to survive on their own. While nearby, universities and private institutions have exploited these same communities with the support of public dollars and public policy.

In the weeks following the night of violence, thousands rallied across the city to protest the legacy of this history. This uprising, and the eyes it focused on the death of yet another black body at the hands of the criminal justice system, brought attention to this long record of segregation and abandonment.

Many have compared it to the 1968 riots that followed Dr. King’s assassination, in which hundreds of businesses across the entire city were vandalized or looted to the tune of approximately $9 million. The people in power were afraid. The National Guard and state sheriffs patrolled the places in which wealth was concentrated or accumulated: Harbor East, Inner Harbor, Johns Hopkins Medical Campus, and the like. Those who sent them there feared that their holdings would be the next target if people felt compelled to correct years of unequal distribution of government favors. The anger of a few had overflowed after years of suppression and repeated injury, disrespect, neglect, and false promises. Indeed, rioting is the voice of those who have not been listened to.

Like mosquitoes on horse dung, the media — local, national, and international — devoured the sensation of the unrest. Baltimore made news in Jamaica, Canada, Poland, China, Russia, Brazil, the UK, and Australia, among other places. We were world famous, we were trending. One year later, what has changed? Did the government address the deeper causes underlying the unrest? That is: mass unemployment, underfunded schools, shuttered recreation centers, poor and inaccessible health care, “affordable housing” filled with rats, mold, and lead managed by slum landlords and speculators — unmonitored and un-reprimanded by government, food deserts, deteriorated infrastructure. Have any substantial changes been made to a criminal justice system that brings injury and death, repeatedly and disproportionately, to black bodies like Mr. Gray's? How have different communities in Baltimore contributed to the process of enacting necessary change at the local level since his killing?

Over the past two weeks, I spoke with thirty-six different people — in-person, and via phone, text, and email — from various spaces and sectors in Baltimore, and asked: what sticks out to you since the uprising last year? Responses came from organizers on the ground, activists with and without non-profit organizations, academics, students, and residents in working-class black communities like Mr. Gray’s Sandtown-Winchester on the west side, and Middle East Baltimore and McElderry Park on the east side. 78 percent of respondents were people of color, 58 percent male.

(The National Guard posted at the Mondawmin Mall. Photo by Marisela Gomez.)

Neighborhoods

The overwhelming response from people in neglected neighborhoods (and from those who live elsewhere when asked about these neighborhoods), was that there has been little or no change. Some felt things were worse in these neighborhoods in regard to policing, drug trafficking and drug use, unemployment, available stores, and safety:

Nothing changed, worse than before. The violence, the separation, people have become more selfish.

Worse, shooting still going on, problems in the house, in the neighborhood, if you know what I mean...things happening right next door and nobody talking.

A shop owner in Sandtown-Winchester responded: “no change, drugs still here...some more foot patrol, since the CVS reopened.” We wondered together why the foot patrol started only after the CVS was reopened: “Who is being protected, corporations or residents”?

Other responses regarding policing painted a picture of continued harassment, and disrespect by police and for police:

Police still sitting in their cars... they [police] still harassing us; when we stand around, sit on our stoop, no change, come through, calling us “niggas,” like they coming to the zoo when they come here, calling us “drug fiends” like we all like that...they the biggest gang around.

Respect me, I respect you...no Officer Friendly round here.

Police need to be watched, they got issues, anger management issues.

Not gonna change how I look [referring to his dreadlocks]. I go to work everyday, they follow, try to arrest me, they see I have a badge for work, don’t care…still harass us. I keep to myself.

One respondent cautioned me: “Don’t go by that street, bunch a guys hang out, the police come, arrest everybody, don’t care who you are, don’t ask no questions, don’t care if you writing a blog or not, just arrest you, they can do that.”

Residents felt that the police continued to hold power over them, to violate their human right to gather, and felt mostly powerless to remedy it. Overwhelmingly, they saw it as a “system thing.” This unrelenting, unchecked harassment fuels the existing fragmentation of community members and between the criminal justice system and those who live under it. One resident felt that instead of harassment, police officers should be building a relationship with community, be role models for young boys and girls, and build trust rather than instill fear. Because police officers are not required to live in the city, people I spoke with felt it was easier for them to separate themselves and treat residents like criminals.

As for physical changes to the neighborhood, residents felt there had been no new development, and that the same houses remained boarded: “You see any new development round here? You see anything? Okay, we got a trash can, each house got one. Wish they would come pick up trash two times each week...no change.” Among interviewees, there was clear understanding of where development was happening: “They [politicians] not trying to invest in our future, they’re building up downtown, wanna get people from other cities, big shot developers don’t have to pay taxes for a long time. They’re not investing in us.”

“Kids have nowhere to go...we used to go from Rec to Rec (recreation center) when I was young, get home and watch TV for an hour, go to bed." Residents and activists confirmed that funding for recreation centers, stores, better schools, affordable housing, and job training was a problem before the uprising and continues to be a problem today.

City Hall

Responses varied about changes at institutional and systemic levels. But everyone took note that the uprising "forced organizations and institutions to finally pay attention to the systemic issues that have been plaguing Baltimore for generations.”

In March 2016, the city council took aim at Baltimore’s “strong Mayor” system, reviving a bill to strip the provisions that allow the Mayor’s office to hold inordinate influence over budgets, salaries, and contracts. If the bill passes, it will redistribute decision-making power equally among the city council, the Mayor, and the comptroller. One academic activist commented: “These aren’t sexy topics, but will have more impact on Baltimore in the next 20 years than anything else.”

While the current mayoral election in Baltimore is being contested by a record number of candidates, people I spoke with felt that none of their platforms contain a real plan to address the systemic issues that resulted in Mr. Gray’s death. As one community resident put it: “Same politicians saying the same thing, nothing different.” Still there was a significant indication of change with a record turnout for early voting this month in Baltimore.

The perception that those in power remained focused primarily on retaining their power was consistently shared by those I spoke with: “I think the state is reorganized, and reforming itself to be ‘prepared’ and cover PR stuff...but power structures remain pretty much intact.”

This sentiment resonated with others who felt that “more are talking about institutional/structural racism without changing operating practices.” This dynamic was elaborated by the diagnosis one respondent offered:

The ways in which white leaders, including Johns Hopkins University, want to “lead” these discussions without understanding the issue...they want to set the rules for discussion in working with those impacted and who have been doing the work and do understand.

One community organizer reflected: “It’s good and necessary to reform the police, but making the nicest police force in the world won’t change the material conditions of black people in Baltimore, and the role of the police will still be to enforce racial/economic inequality.” This deep-rooted cause of the uprising continues to be ignored, as another academic activist suggested:

There has been little public discussion about the root causes of Baltimore's inequity: segregation and serial forced displacement...We're not changing the fundamental problems of the city when we don't even acknowledge they exist.

Trials for the six officers indicted in Freddie Gray’s murder — let alone the process of remaking the system of policing — remain unfinished. The first trial for an indicted officer resulted in a hung jury, with no new trial scheduled to date. The trial for a second officer was halted pending appeal and has not re-started. The remaining officers have not yet been tried.

Many feel that these delays indicate that even when police are indicted for the injury and killing of black and brown people, they will continue to avoid punishment. Several activist groups organized a sit-in at city hall in October 2015 to protest the lack of police accountability and transparency, existing tensions between police and residents, and the city’s failure to respond to activists’ request to meet face-to-face about the confirmation of a new police commissioner. This challenge continued to raise awareness nationally and focus attention on police accountability, corruption, and violence.

Overall, there was a sense that state and capital are continuing business as usual. This is exemplified by the current development proposed in Port Covington. The developer, billionaire owner of corporate giant Under Armour, is seeking $535 million in tax increment financing. The Mayor’s office and the Baltimore Development Corporation are not revealing the details of the negotiation, continuing the lack of accountability and transparency and the neoliberal policies that funnel public dollars to private interests, with minimal public oversight. While the city has local hiring and affordable housing requirements for new developments, this developer, like many others, has been exempted from these requirements.

Without an effort to systematically analyze, let alone remedy, what is needed to address the legacy of disinvestment and segregation that shapes Baltimore — and as long as the police department’s budget is three times that of other departments, officials ensure that police brutality will remain the only way the city responds to communities’ needs.

The Funding Industry

In terms of of the funding industry, there was a consistent critique of where the money coming into Baltimore after the uprising was going. Responses highlighted that the same main players and institutions were getting funding: “They [NGOs and local funders] became the face of the movement to change Baltimore, and that is not where the work is getting done. This is not to accuse them of being deceitful (although that is not beyond them), but now we get caught in this trickle-down funding.” Funding for organizing work at the grassroots level is still missing, and instead service and beautification projects appear to be trending:

The uprising led to millions of dollars being poured into Baltimore. This city became America's pet project for improvement and renovation, but where has the money gone?

It’s like they don’t really want to see communities empower themselves, want them to be enslaved by the white man forever, through crumbs...another level of begging

No new real money for groups doing organizing — Casey [the Annie E. Casey Foundation] and OSI [Open Society Institute] gave some small $$ [amount], like $20,000 per to established groups but that money hasn't been large enough to significantly increase the capacity of people to organize neighborhoods, around issues, etc.

The world of NGOs and philanthropists reflects the legacy of wealth accumulated from the exploitation of racial minorities and the poor, and must be pushed to fund genuinely local, grassroots organizations.

Organizers and activists

A new wave of activism in Baltimore emerged from the fire of the uprising, raising individual and collective consciousness across different identity groups:

More conversations being had, maybe it was there already, but now people feel more compelled to raise it.

I am more certain than ever that blackness is the fulcrum and that the Asian communities MUST stand in solidarity with the black community to address anti-black racism and the anti-black logic of model minority politics that uphold white superiority.

Already existing activist organizations increased their efforts and began connecting across identities and issues, building a solidarity movement. The severe social fragmentation that existed before the uprising temporarily halted in the first two months that followed. One year out, fragmentation has returned, but at lower levels than before. The greatest fragmentation among activists and groups continues between the grassroots movement-builders and what some refer to as the “activist elite.” Elite activists may not be involved directly with affected communities and are at times unaware and unwilling to engage in grassroots community organizing:

Most of the work that’s come out of it [the funding of organizing efforts since the uprising] prioritizes the voices of sort of intellectual elite black actors who are doing a great job mobilizing, but not really building the capacity of black communities to determine their own priorities and demands... aren’t willing to take the time to build the relationships necessary for actual movement building.

The youth have stood up in force and taken their responsibility for change to heart and mind. They are building a powerful movement across the city:

Among community groups, thought leaders, and especially youth, there is a groundswell of innovation, self-reflection, and reform that is building... The uprising will be remembered as a turning point for many of the future leaders of this city, and I love that.

In a reflection of this youth activism, the Algebra Project, along with other groups, declared a district-wide school walk-out on April 14 to protest standardized testing as an example of institutional racism. On April 13, a group of fifty activists took over a vacant house in Sandtown-Winchester near where Mr. Gray was arrested, and turned it in to a community center. They named it after Harriet Tubman, in tribute to those who take their liberation with their own hands.

Others I spoke with felt that the focus on youth-lead organizing and the funding of youth-focused projects had ignored the elders who have been doing this work for decades. Still others suggested that there was a healthy dynamic between between older and younger activists. “I would say that Baltimore is unique,” one community leader said, “because there are substantive connections between younger activists and elders with movement history.”

Several people told me that black-led organizing and activism had continued to grow stronger in the year since Mr. Gray’s death:

Baltimore seems more grounded in black-led grassroots leadership of our movement here, as opposed to foundations making decisions about our agenda.

Black folks and others are accelerating cooperative economic strategies.

At the same time, in a city that is 66% Black, many political organizations continue to be led by white people, some who still ignore the necessity of making racial justice the fundamental base for liberatory projects in Baltimore; some who are unclear about their role as allies in the struggle for racial justice.

The sense that everyday white people were taking notice, waking up, and seeking more information was offered by several of those I spoke with, most of them white themselves: “[There is] much more interest from ‘regular people’ (I'm thinking here of folks I work with, in all kinds of roles, and people in my building, or that I run into at my children's school, etc) in understanding how the city has come to be where we are.”

Others complained of the ways in which the uprising had been appropriated and put to misleading or inane uses:

I'd say that one thing that comes to my mind is the way that "since the uprising" seems to have become a shorthand way of referencing a particular timeframe or cultural moment without using the uprising to actually contextualize the conversation in any meaningful way... the reference seems like an empty gesture at best, or even a deliberate misdirect meant to (falsely) imply that their comments are informed by the conditions surrounding the uprising.

Such appropriation by individuals can be linked to the appropriations made by powerful institutions that have begun lamenting structural racism without changing any of their own policies and practices.

(The National Guard patrols a rally. Photo by Marisela Gomez.)

Violence and change

Another perception shared by interviewees is that uprising and the responses to it suggest that the powerless need to express anger or act violently for people with power to take notice, and for change to occur:

Does it mean that getting angry you get what you want, you have to be violent to be listened to...[the rioting] sends this message, this worries me.

Is violence the means to change?

A strong argument can be made for setting things on fire as a way to get a hearing when you have a legitimate grievance [this year every politician wanted to talk to this youth group]...This is troubling in the extreme. But it is what leaps out at me every day...We hope to build on the increased attention and funding to build something sustainable without fires. Time will tell.

One respondent, a white college student who identified himself as a "hipster," reflected on the apparent permission the uprising granted some to finally demand what they feel is needed: “Since the uprising, people on the street begging have been more aggressive than before...I always wondered why people weren’t more angry [about the history and current conditions of racism]

While the rallies that began in the week following Mr. Gray’s death and which followed for many weeks after were always peaceful, the looting and property damage on April 27 reflected the violence inflicted on many communities in Baltimore (including the police violence met by many peaceful protestors). And while some of the rhetoric is changing, the violence that ignited the uprising continues to be inflicted by the more-or-less unaltered criminal justice system.

After uprisings that involve any degree of property destruction, the default question posed by the media, politicians, and even well-meaning institutions of white supremacy is: when will the violence stop? It would be asked better the other way around, posed to the institutions that inflict and manage the state and economic violence that is central to the United States as it exists: Is violence what is required to change you?

Violence does not condone violence, as Baltimore modeled when thousands came out to non-violent protests that followed the rioting, showing the world that one moment of violence is not who we are. We learned that connecting our struggles is more powerful than maintaining our silos. The questions still out are: Have capitalists and those with real power inside the state learned anything since the police murder of Freddie Gray on April 12, 2015? Or will the structural violence continue? What is clear is that one year later, Baltimore is becoming increasingly organized, from the ground up. Mr. Gray’s death began a movement; one that Baltimore activists and organizers have confirmed will not be swept under the rug by the racist and capitalist machine.