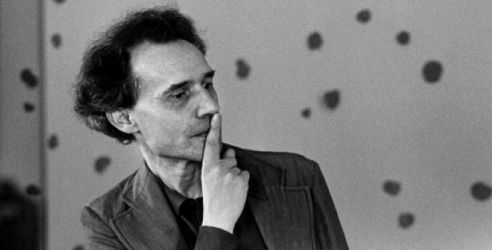

Jacques Rivette (1928-2016)

Jacques Pierre Louis Rivette was born in Rouen, Seine-Maritime, France. The filmmaker and critic died today aged 87, and had reportedly had Alzheimer’s disease for some years. In 1953 Rivette joined other young Turks François Truffaut, Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol as a writer on the influential journal Cahiers du Cinéma, at the time edited by André Bazin. Rivette became editor of Cahiers in 1963, succeeding Eric Rohmer to steer the magazine to greater political engagement reflective of his radical politics as well as the climate of the time. Verso presents an extract from Emilie Bickerton's A Short History of Cahiers du Cinéma about the journal's new directions under Rivette's editorship.

Rivette’s putsch

Rivette was the leading figure who charged Rohmer with allowing a confort de caste, or complacency of thought, to set in that left Cahiers isolated from the dynamic present. He wanted to attend to alternative sources of innovation. New cinema from Europe (Bertolucci, Pasolini, the Polish ‘workshops’), Brazilian cinema nôvo and Direct Cinema from around the world began to be addressed. Rejecting pure cinephilia, he sought an opening of the journal to broader intellectual movements. After the failed attempts by Truffaut and Doniol-Valcroze in 1962 to encourage Rohmer to reassess some of the old Cahiers tenets, Rivette mounted an alternative team. The end of Rohmer’s reign was undignified for a man of such elegance in writing and directing. It was also cruel. He put together number 144 at the same time as Rivette’s competing team worked on their issue, and, in a lonely final flurry, wrapped up his version in his pyjamas after a white night at the office. It was published, but it was to be his last. Rivette had the support of the editorial board and, by now, of most of the contributing critics. Cahiers 145 announced the change of editors: Rivette was at the head and Rohmer out the door.

In his first editorial in August 1963, Rivette responded immediately to the problem Godard had raised in his 1962 interview: what had made Cahiers was ‘its position in the front line of battle’, but with everyone now largely in agreement with Cahiers’ arguments, ‘there isn’t so much to say’. Positions that had been high stakes in the fifties had become ‘dogma and system’, Rivette reiterated, and criticism had to evolve. The postures that had been adopted ‘from a tactical point of view’ were now caducs—clapped-out. Later he would describe how the experience of watching his Paris Belongs to Us in a crowded cinema in 1960 had changed his notions of film criticism: it had to consider the context in which films were made and seen. The cinephile approach, too awestruck by the screen, precluded this.

Such are the perils of the ‘pure gaze’ attitude that leads one to complete submission before a film . . . like cows in a field transfixed by the sight of passing trains, but with little hope of ever understanding what makes them move.

Engaging with the changing social landscape of which film was a part, both in its production and its reception, meant a break with the old agenda. Cinema could not be understood in isolation and, most importantly, it need not be. Cahiers’ first ten years had laid the foundation for taking film seriously; now criticism had to grasp the new points of tension.

Cinema’s Copernican revolution

The opening that characterized Rivette’s editorship between 1963 and 1965 involved a new receptivity to other disciplines and intellectual currents: anthropology, literary theory and, a little later, the psychoanalysis of Lacan and concepts of ideology developed by Althusser. All were brought to bear on understanding the nature of cinema as a twentieth-century art form. Rivette was inspired by the array of new styles and visions emanating from the other arts. Abstract Expressionism had arrived in Paris via exhibitions by Jackson Pollock in 1959 and Mark Rothko in 1962; music, too, was exploring new forms, with Pierre Boulez’s Domaine musical concerts, Schoenberg’s Moses and Aaron, and the works of Webern, Berg and Stockhausen. Modern cinema, Rivette went so far as to say, was musical. In February 1964 a full section in Cahiers was devoted to the soundtrack alone. Whereas the politique had been established through long conversations with practicing auteurs, the new masters to be invited to face a Cahiers interrogation were drawn from outside the cinematic environment. As well as Roland Barthes, Claude Lévi- Strauss and Pierre Boulez, Jean-Paul Sartre was invited for interview, though he declined.

Bazin’s maxim, ‘cinema is a language’, was re-examined within the linguistic paradigms of structuralism. This approach conceived of film as containing codes and modes of expression that worked according to the same mechanism as signs and syntax. Such codes permitted meaning to exist in films, but were communicated in various and complex ways, which the concept of mise en scène was deemed too vague to fully explain. Alternatives were proposed, such as Pasolini’s long text in 1965 describing a nascent ‘poetic cinema’ that would be the maturation of neo-realism; the rejection of conventional narrative ‘prose’ and the use of ellipses in the work of Antonioni or Resnais made interpretation essential, almost to the point of erasing the significance of the auteur. Interviewed by Cahiers, Barthes affirmed that ‘man is so fatally bound to meaning that freedom in art might seem to consist . . . not so much in creating meaning as suspending it’. Resnais’s Last Year in Marienbad had marked a ‘Copernican revolution’ for Cahiers critics. As with modernist painting, where ‘the task of the painter is no longer to paint a subject, but to make a canvas’, so with the camera: ‘the film-maker’s job is no longer to tell a story, but simply to make a film in which the spectator will discover a story’. The audience was now becoming ‘the hero of the film’. Bresson’s Au hasard Balthazar was celebrated for its economy of signification and its subtractive quality:

[he] wants each image to express only what he wants to make it express, after eliminating what one might call ‘noise’ . . . he is forced to resort to a style that eliminates inevitably ambiguous facial expressions, too loaded with meaning . . . Ellipsis becomes obligatory, because he cannot dwell too long on any one face.

A review of Buñuel’s Belle de jour made clear the new critical tools being employed. The article was saturated with structuralist language: ‘the film is articulated through two formal series which must be read in abstraction from any “level” or “hierarchy”’. Jean- Louis Comolli, in an early contribution to the journal, confirmed his transition from Rohmerian to Rivettian attitudes: citing Blanchot, Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty and Jung, he proposed a relationship between philosophy and cinema, a way of feeling the film by thinking it. New work should aim not to lull its audience with the comfort of ritual within the darkened auditorium, but to unsettle and provoke greater reflection. Rivette, too, welcomed such disturbance: ‘the role of cinema is to destroy myths . . . to take people out of their cocoons’.

The new works by Federico Fellini, Miklós Jancsó, Jean-Marie Straub, Godard and Tati were among the strongest examples of this ‘cinema of signification’, being understood through a Barthesian perspective. They all reconstituted the relationship to narrative within the film, and consequently changed the engagement of the audience with the fiction. ‘A film is always presented in a closed form’, Rivette would later explain. It is a certain number of reels, screened in a particular order. However, within this exist any number of circulating meanings, functions and forms which can remain unresolved. This incompleteness was, for Rivette, the real strength of modern cinema and what directors should aim to achieve: a film or a work should not exhaust its coherence, close in on itself; ‘it must continue to function, and to create new meanings, directions and feelings.’

The next generation

Under Rivette’s editorship, the keynote articles being published were by the new generation of cinephiles drawn into the Cahiers orbit in the early sixties. Ironically, since these would be the critics behind the putsch, many had been invited to write for the review by Jean Douchet (who also had to leave when Rivette took over). Omnipresent on the Parisian cine-club scene, Douchet met many young cinephiles and budding critics whom he encouraged to write for Cahiers. Among the most influential arrivals were two medical students from Algeria: Jean- Louis Comolli (b. 1937) and Jean Narboni (b. 1941). Both men had cut their teeth at the Ciné-club d’Alger before coming to Paris to study in 1961. Another new arrival was Serge Daney (b. 1944). A Cahiers reader since the age of fifteen, while still a teenager Daney had started his own short-lived film journal, Visages du cinéma, with his friend and fellow-devotee Louis Skorecki. Unprecedented for Cahiers, the latter two were adventurous travellers and their early contributions were as roving critics, reporting back from India, Africa and America. Bernard Eisenschitz was a Russian and German specialist, and helped to fill a much-needed hole in Cahiers’ coverage of these cinemas when he arrived in 1967. Michel Delahaye was a student of Lévi-Strauss and admirer of Jean Rouch’s ethnographic cinema. Nouveau roman author Claude Ollier and critic Jean-André Fieschi—who was close friends with Comolli and Jean Eustache—also came aboard, Fieschi embracing an avant-garde ethic that rejected the ‘illusory of beauty’ of the mise en scène. All were equipped with a broader range of theoretical interests, and in contrast to the yellow years, a number would remain critics, as opposed to evolving into critics– cinéastes as the previous cohort had.

This new crop subsequently discarded the whole notion of mise en scène, much as abstract painters had done away with figuration. Initially, the mise en scène had been invoked as a reaction against the critical tendency to talk exclusively in terms of themes and subjects, emphasizing the idea that cinema is also something which one sees on the screen. It provided a means of understanding film as the expression of a specifically personal vision. By the sixties, the consensus at Cahiers was that the concept had been abused to the point of nonsense. Echoing the early reservations of André Bazin in 1953, when he argued that Huston’s The Red Badge of Courage was far better than either Strangers on a Train or Rope because ‘the subject also counts for something’, Rivette complained that mise en scène was ‘now used to suggest that as long as the camera movement can be called sublime, it makes no difference if the story is fatuous, the dialogue idiotic and the acting atrocious.’ Labarthe called for the end of mise en scène as a concept, finding it debilitating for current critics who had become ‘victims’ and ‘prisoners’ of their own language.

Turning on the lights

What critics were now expected to grasp were the external elements: the act of contextualizing a work was paramount; the sense of what environment a film had come out of, its connection with the world, and its expression of this. National cinemas were singled out as objects of study; from each film was extrapolated the particular economic, social and political conditions out of which it had emerged, and its entire production history was tracked. Out with the esprit de Cinémathèque, where bodies and minds were shut away from the outside world; it was time for the lights to come on. Godard characterized the shift accordingly:

The approach to criticism ten years ago was like Mendeleev’s classification of the elements: everyone thought there were seven or eight of them and the New Wave claimed there were far more than that, two hundred or three hundred. And from that point onwards, modern chemistry was born.

Rohmer had traced the shift from ‘marble to celluloid’, but with a view to make cinema part of the musuem. The transformation Godard described was more dramatic. Modern cinema was unpredictable, capricious, open to freer interpretation, and its criticism had to adjust. Interesting and innovative work was also to be found elsewhere. By the mid-sixties, the auteurs that Cahiers’ Hitchcocko- Hawksians had spotlighted within Hollywood were growing old and disappointing their fans with their later works—Ray’s 55 Days at Peking, Hawks’s Man’s Favourite Sport, Ford’s Cheyenne Autumn, Preminger’s Exodus and In Harm’s Way, Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain. The cinematic horizon had expanded to India (Satyajit Ray), Japan (Kurosawa), Brazil (Rocha); Czechoslovakia (Milos Forman, Jan Svankmajer), Poland (Polanski, Wajda), the USSR (Tarkovsky), Germany (Danièlle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub), Sweden (Bergman), Italy (Antonioni, Fellini, Pasolini) and within France itself (Buñuel, Marker, Resnais, Rouch).

Working with cine-clubs, in 1966 Cahiers introduced a new international section, covering the latest releases from around the world. Comolli welcomed the advent of a new political cinema in which one could see ‘the sharp point of a struggle which is not only artistic but which involves a society, a morality, a civilization’. To understand these, the triangle of film–public–auteur had to be broken. Originally the New Wave had based its success on reaching as wide an audience as possible, because this marked the distribution of a work of art, and not just qualité française. But audiences had been in decline since the start of the sixties. The appetite for New Wave films decreased rapidly, and mass viewing of the moving image was shifting progressively to television. New films from around the world did not always have a popular touch or a global reach. At Cahiers this was immaterial—it was believed the films could find their public later. This shift in the Cahiers position vis-à-vis the public made it far more wary of the mainstream—the interesting works were moving to, being increasingly forced to, the margins. Innovation and creativity would more likely be found outside the system than within it.