Thought is the courage of hopelessness: an interview with philosopher Giorgio Agamben

Giorgio Agamben's philosophy ranges across disciplines, traditions, and topics in order to develop critical philosophical and political questions. Moving from religion, law, and language to capitalism, work, sovereignty, and the economic crash his thought sheds new light on the contemporary condition. This, his most recent interview, is no exception. He sat down with Juliette Cerf in Rome to discuss and clarify many of his positions.

Thought is the courage of hopelessness: an interview with philosopher Giorgio Agamben by Juliette Cerf

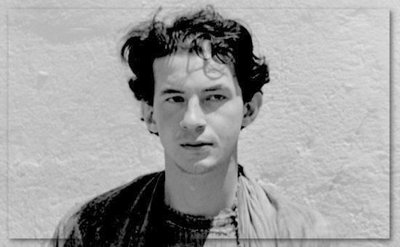

As the church bells ring out in Trastevere, where we have fixed our appointment, his face comes to mind... Giorgio Agamben appeared as the apostle Philip in Pier Paolo Pasolini's The GospelAccording to St. Matthew (1964). At that time the young law student, born in Rome in 1942, hung around with the artists and intellectuals grouped around the author Elsa Morante. The dolce vita? A moment of intense friendships, in any case. Little by little the jurist turned toward philosophy, following Heidegger's seminar in Thor-en-Provence. He then threw himself into editing the works of Walter Benjamin, a thinker who has never been far from his thought, as well as Guy Debord and Michel Foucault. Giorgio Agamben thus became acquainted with a messianic sense of History, a critique of the society of the spectacle, and a resistance to biopower, the control that the authorities exercise over life – over citizens' very bodies. Poetical as it is political, his thought digs down for archaeological evidence, making his way back through the whirlwind of time, down to the origins of words. Author of a series of works collected under the Latin title Homo sacer, Agamben travels through the land of law, religion and literature but now refuses to go... to the United States, to avoid being subjected to its biometric controls. In opposition to any such reduction of a man to his biological data, Agamben proposes an exploration of the field of possibilities.

JC: Berlusconi has fallen, like several other European leaders. Having written on sovereignty, what thoughts does this unprecedented situation provoke in you?

GA:Public power is losing legitimacy. A mutual suspicion has developed between the authorities and the citizen. This mounting mistrust has overthrown some regimes. The democracies are greatly worried: how else can we explain that they have a security policy twice as bad as Italian Fascism had? In the eyes of power, every citizen is a potential terrorist. Never forget that the biometric apparatus, which will soon be inserted in every citizen's identity card, was firstly created to control recidivist criminals.

Is the crisis linked to the fact that the economic has stolen a march on the political?

To use the vocabulary of ancient medicine, the crisis marks the decisive moment of the illness. But today, the crisis is no longer temporary: it is the very drive of capitalism, its internal motor. The crisis is continually ongoing, since, like other exceptional mechanisms, it allows the authorities to impose measures that they would never be able to get away with in a normal period. The crisis corresponds perfectly – funny though it may seem – to what people in the Soviet Union used to call the 'permanent revolution'.

Theology plays a very important role in your reflection today. Why is that?

The research projects that I have recently undertaken have shown me that our modern societies, which claim to be secular, are, on the contrary, governed by secularised theological concepts, which act all the more powerfully because we are not conscious of their existence. We will never grasp what is going on today unless we understand that capitalism is, in reality, a religion. And, as Walter Benjamin said, it is the fiercest of all religions because it does not allow for atonement... Take the word 'faith', usually reserved to the religious sphere. The Greek term corresponding to this in the Gospels is pistis. A historian of religion trying to understand the meaning of this word was taking a walk in Athens one day, when suddenly he saw a sign with the words 'Trapeza tes pisteos'. He went up to it, and realised that this was a bank: trapeza tes pisteos means: 'credit bank'. This was illuminating enough.

What does this story tell us?

Pistis, faith, is the credit that we have with God and which God's word has with us. And there is a major sphere in our society that entirely revolves around credit. This sphere is money, and the bank is its temple. As you known, money is nothing but a credit: on notes in dollars and pounds (but not on the euro: and that should have raised our eyebrows...) you can still read that the central bank will pay the bearer the equivalent of this credit. The crisis was unleashed by a series of operations with credits that had been re-sold dozens of times before they could be realised. In managing credit the Bank – which has taken the place of the Church and its priests – manipulates the faith and the confidence of Man. If politics is today in retreat, that is because financial power, substituting itself for religion, has kidnapped all faith and all hope. That is why I am carrying out research on religion and law: archaeology seems to me to be the best way of accessing the present. Europeans cannot access their present without measuring themselves up to their past.

What is this archaeological method?

It is a search for the archè, which in Greek means 'beginning' and 'commandment'. In our tradition, the beginning is both that which gives birth to something and that which commands its history. But this origin cannot be dated or chronologically situated: it is a force that continues to act in the present, just as infancy, according to psychoanalysis, determines the mental activity of the adult, or like how the big bang, which, according to astrophysicists, gave birth to the Universe, continues expanding even today. The example typifying this method would be the transformation of the animal into the human (anthropogenesis), that is, an event that we imagine necessarily must have taken place, but has not finished once and for all: man is always becoming human, and thus also remains inhuman, animal. Philosophy is not an academic discipline, but a way of measuring oneself up to this event that never stops taking place and which determines the humanity and inhumanity of mankind: very much vital questions, in my view.

Is this vision of becoming human, in your works, not rather pessimistic?

I am very happy that you asked me that question, since I often find that people call me a pessimist. First of all, at a personal level, that is not at all the case. Secondly, the concepts pessimism and optimism have nothing to do with thought. Debord often cited a letter of Marx's, saying that 'the hopeless conditions of the society in which I live fill me with hope'. Any radical thought always adopts the most extreme position of desperation. Simone Weil said 'I do not like those people who warm their hearts with empty hopes'. Thought, for me, is just that: the courage of hopelessness. And is that not the height of optimism?

According to you, to be contemporary means to perceive the darkness of one's epoch and not its light. How should we understand this idea?

To be contemporary is to respond to the appeal that the darkness of the epoch makes to us. In the expanding Universe, the space that separates us from the furthest galaxies is growing at such speed that the light of their stars could never reach us. To perceive, amidst the darkness, this light that tries to reach us but cannot – that is what it is to be contemporary. The present is the most difficult thing for us to live. Because an origin, I repeat, is not confined to the past: it is a whirlwind, in Benjamin's very fine image, a chasm in the present. And we are drawn into this abyss. That is why the present is, par excellence, the thing that is left unlived.

Who is the supreme contemporary – the poet? Or the philosopher?

My tendency is not to oppose poetry to philosophy, in the sense that these two experiences both take place within language. The home of truth is language, and I would distrust any philosopher who would leave it to others – philologists or poets – to look after this home. We must take care of language, and I believe that one of the essential problems with the media is that they show no such concern. The journalist, too, is responsible for language, and will by judged by it.

How does your latest work on liturgy give us a key to the present?

To analyse liturgy is to put your finger on an immense change in our way of representing existence. In the ancient world, existence was right there – something present. In Christian liturgy, man is what he must be and must be what he is. Today, we have no other representation of reality than the operational, the effective. We no longer conceive of an existence without effect. What is not effective – workable, governable – is not real. Philosophy's next task is to think of a politics and an ethics that are freed of the concepts of duty and effectiveness.

Thinking about inoperativeness, for example?

The insistence on work and production is a malign one. The Left went down the wrong path when it adopted these categories, which are at the centre of capitalism. But we should specify that inoperativeness, as I conceive it, is neither inertia nor idling. We must free ourselves from work, in an active sense – I very much like this French word désoeuvrer. This is an activity that makes all the social tasks of the economy, law and religion inoperative, thus freeing them up for other possible usages. For precisely this is proper to mankind: writing a poem that escapes the communicative function of language; or speaking or giving a kiss, thus changing the function of the mouth, which first and foremost serves for eating. In his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle asked himself whether mankind has a task. The work of the flute player is to play the flute, and the cobbler's job is to make shoes, but is there a work of man as such? He then advanced his hypothesis according to which man is perhaps born without any task; but he soon abandoned it. However, this hypothesis takes us to the heart of what it is to be human. The human is the animal that has no job: it has no given biological task, no clearly prescribed function. Only a powerful being has the capacity not to be powerful. Man can do everything but does not have to do anything.

You studied law, but all your philosophy seeks, in a sense, to free itself from law.

Leaving secondary school, I had just one desire – to write. But what does that mean? To write – what? This was, I believe, a desire for possibility in my life. What I wanted was not to 'write', but to 'be able to' write. It is an unconscious philosophical gesture: the search for possibility in your life, which is a good definition of philosophy. Law is, apparently, the contrary: it is a question of necessity, not of possibility. But when I studied law, it was because I could not, of course, have been able to access the possible without passing the test of the necessary. In any case, my law studies came to be very useful for me. Power has dropped political concepts in favour of juridical ones. The juridical sphere never stops expanding: they make laws on everything, in domains where it would once have been inconceivable. This proliferation of law is dangers: in our democratic societies, there is nothing that is not regulated. Arab jurists taught me something that I liked very much. They represent law as a sort of tree, with at one extreme what is forbidden and, at the other, what is obligatory. For them, the jurist's role is situated between these two extremes: that is, addressing everything that one can do without juridical sanction. This zone of freedom never stops narrowing, whereas it ought to be expanded.

In 1997, in the first volume of your Homo Sacer series, you said that the camp is the norm of our political space. From Athens to Auschwitz...

I have been criticised a lot for this idea, that the camp has replaced the city as the nomos (norm, law) of modernity. I was not looking at the camp as a historical fact, but as the hidden matrix of our society. What is a camp? It is a part of the territory that exists outside the juridical-political order, a materialisation of the state of exception. Today, the state of exception and depoliticisation have penetrated everything. Is the space under CCTV surveillance in today's cities public or private, interior or exterior? New spaces are being created: the Israeli model in the occupied territory, composed of all these barriers excluding the Palestinians, has been transposed to Dubai to create hyper-secure islands of tourism...

At what stage is Homo sacer?

When I began this series, what interested me was the relation between law and life. In our culture, the notion of life is never defined, but it is ceaselessly divided up: there is life as it is characterised politically (bios), the natural life common to all animals (zoé), vegetative life, social life, etc. Perhaps we could reach a form of life that resists such divisions? I am currently writing the last volume of Homo sacer. Giacometti said something that I really liked: you never finish a painting, you abandon it. His paintings are not finished; their potential is never exhausted. I would like the same to be true of Homo sacer, for it to be abandoned but never finished. I think, moreover, that philosophy should not consist too much of theoretical statements – theory must sometimes display its insufficiency.

Is this the reason why as well as your theoretical essays you have always also written shorter, more poetic texts?

Yes, exactly so. These two registers of writing do not stand in contradiction, and, I hope, they often even cross paths. It was starting from a big book, The Power and the Glory, a genealogy of government and economics, that I was forcefully struck by this notion of inoperativeness, which I tried to develop in more concrete fashion in other texts. These crossed paths are the whole pleasure of writing and thinking.

Interviewed in French by Juliette Cerf. See the original here.